Pete Cannell reviews Nicholas Beuret’s book, which critiques green capitalist transition pathways and sets out strategies to fight back against them.

This article was first published on the rs21 website.

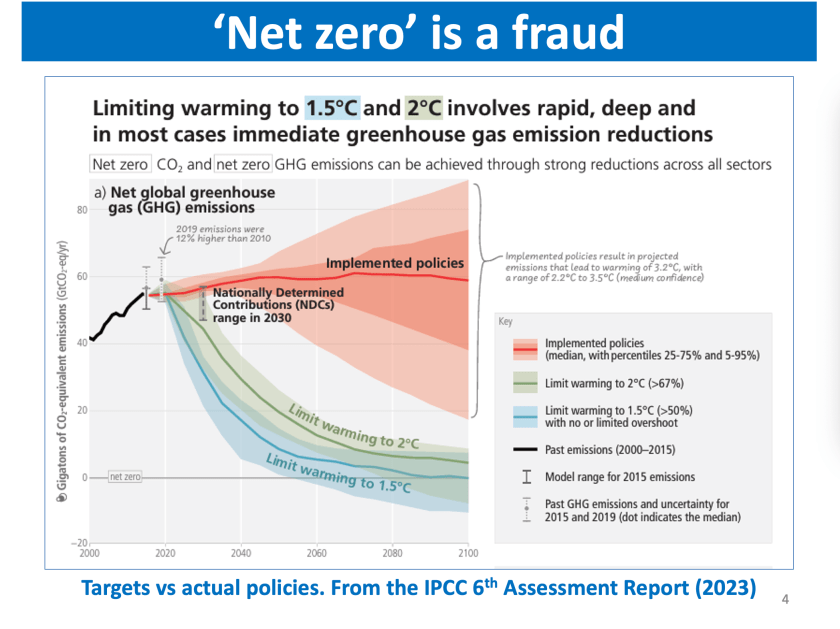

Another year, another COP – this time in Brazil. Since the global climate summits began in 1995, levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide have climbed inexorably. They now stand approximately 20 per cent higher. It looks like 2025 will have been the year when the 1.5 degree increase in global average temperature was breached. Yet in the face of pressure from petro-states and fossil capital the final statement from COP30 could scarcely hint at the need to end the use of fossil fuels.

The need for a new climate movement

Or Something Worse by Nicholas Beuret is an uncompromising call for a reinvigorated climate movement that faces up to the reality of this crisis and adopts new tactics which reflect the urgency of the situation we find ourselves in. He has no time for the professional optimism of the NGOs looking for slivers of hope in the dismal outcomes of each annual COP conference. In the first half of the book Beuret lays out the stark reality of the consequences of years of inaction. Not just extreme weather events, but crop failures, water shortages and everywhere higher food prices – all of which hit the poorest hardest. The climate crisis is here now, and it has real material impacts on the lives and livelihoods of people around the world.

In the introduction Beuret argues that ‘What is needed is for us to understand the shape of the transition, to map its contours and contradictions … in order to organise not against it, but through it.’ He goes on to explain that ‘we are in the midst of a profound social, political and economic transition’. But throughout the book he describes this process as a ‘green transition’. He makes it clear this is a capitalist transition – one that prioritises the interests of dominant groups and reinforces the status quo. However, I found the green tag unhelpful and a barrier to understanding.

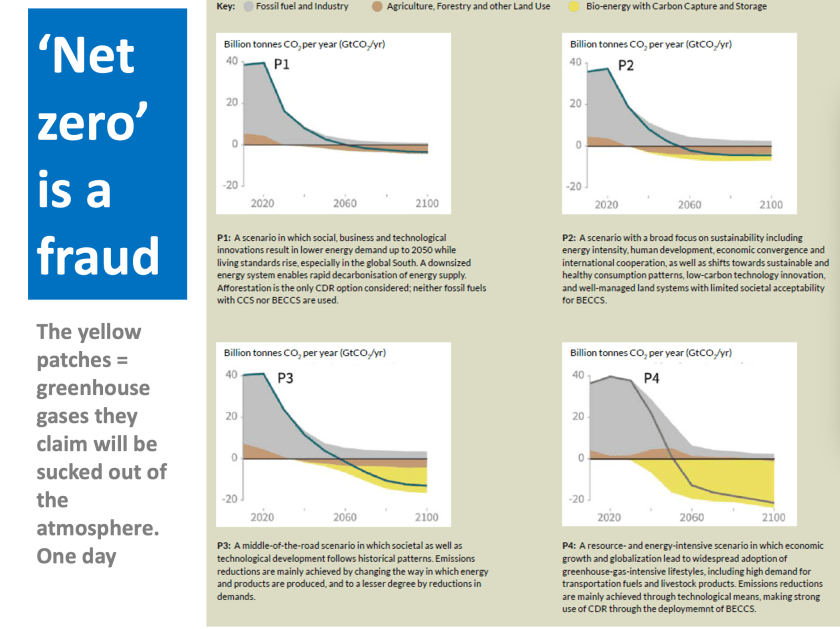

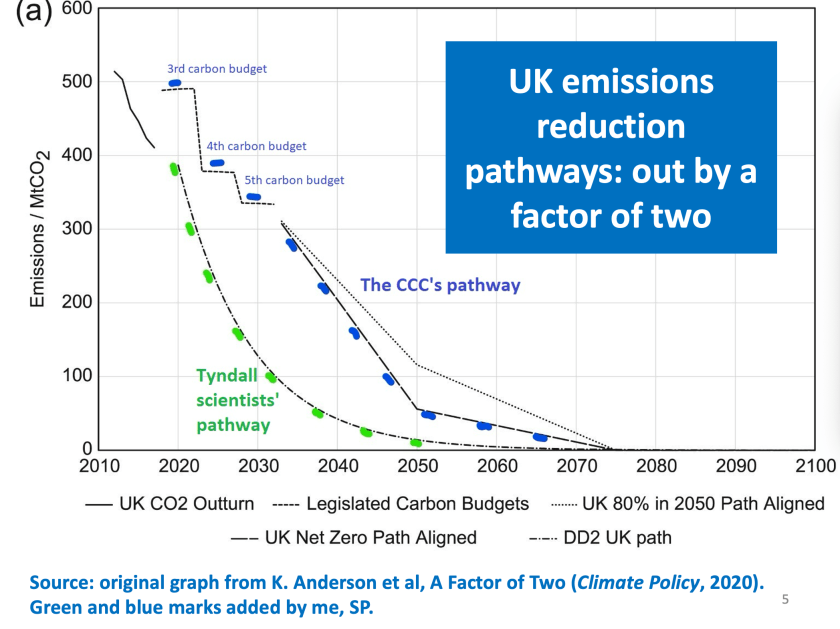

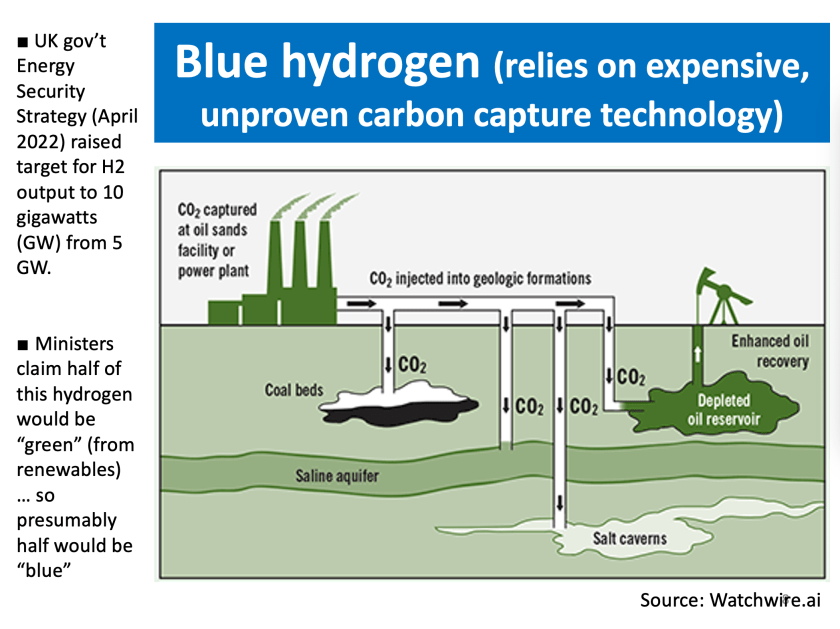

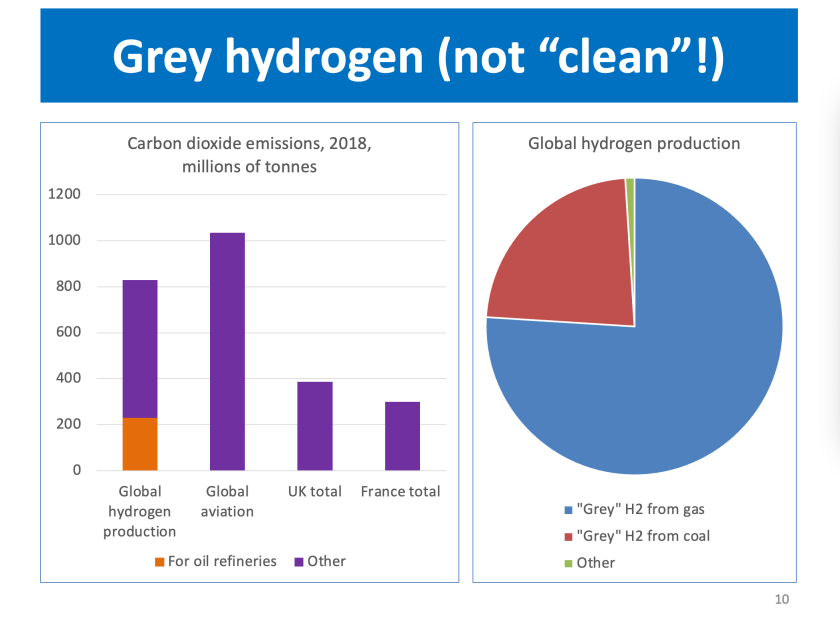

The first three chapters provide a bleak assessment of the impact of the crisis, using the steel plant at Port Talbot as an example. Together, they paint a compelling picture of the depth and extent of the crisis. In my view, however, the overall framing in terms of green transition has a distorting effect. Part of Beuret’s case is that countries in the Global North bought into the necessity of green transition while establishing a social contract predicated on a state-promoted transition that stimulates economic growth. I think the idea that there was ever such a social contract is overstated. It’s true that governments engaged in green transition rhetoric, some even acknowledging the climate emergency in response to the mass movement of young people that exploded in 2018 and 2019. But most often they put their faith in the market to achieve a transition framed by the priorities of fossil capital. For example, in Britain and elsewhere strategic investment was directed towards hydrogen, carbon capture and storage, and nuclear. So, we can talk about a process of economic transition that involves increased utilisation of wind and solar power – but it is not clear that there is any meaningful sense in which this is a greentransition either in intention or in practice.

We are witnessing a rapid growth in new ‘green’ technology. Globally, capital expenditure by the fossil fuel industry is down to just under $600 billion a year, a decline of 40 per cent in the last decade. Yet at the same time (witness COP30) fossil capital is digging in for the longer term. Beuret describes very well how in the Global North countries are pushing down carbon emissions within their territory while pushing fossil fuel use and resource extraction onto the Global South. What’s happening looks like previous capitalist energy transitions – wood to coal (and wood), coal to oil (and coal) – that Jean-Baptiste Fressoz criticises in More and More and More. Can we call this a ‘green transition’ when energy consumption globally continues to rise, and when the expected future use of fossil fuels goes far beyond the level at which limiting global temperature rise to two- or even three-degrees remains achievable?

At one point Beuret talks about governments in the Global North becoming more interventionist and allocating billions of dollars to support national industrial policies. Yet this conflicts with what he says later on in the chapter on the ‘transition economy’, where he explains that in general, policy goals for green transition are almost always left to the market; he’s also scathing about liberal utopianism that assumes that governments or markets will respond to the crisis rationally. This reflects a weakness in the book’s analysis of the economics of the climate crisis. It seems as if Global North ‘transition’ initiatives are the main driver of change rather than mediated through a world economic system which is in flux. Rather than framing what’s taking place as a ‘green transition’, I would argue that technological and economic transition driven by the climate crisis is shaped by and mediated through the changing contours of global imperialist competition following five decades of neo-liberalism. Crude Capitalism, published earlier in 2025, has a much firmer grasp on the geopolitics of the world economy, the deep entanglement of fossil fuels with the military industrial complex and the shifting balance of power between major imperialisms, principally but not exclusively between the US and China.

Arguably, another weakness of the economic analysis is the discussion of the impact of transition on jobs and employment. Beuret accurately describes how the so-called ‘green transition’ has had a negative effect on employment and working conditions. He goes further, however, to claim that as jobs related to the fossil fuel economy decline:

… while there are many ways to cushion the blow, from reduced working weeks to building up the social economy to strengthening social services and public provisioning, none of these would amount to the creation of an equal number of similar jobs.

No evidence is given for the claim that whatever is done there will be a net loss in jobs. In fact there is strong evidence from a number of studies that suggests that a genuine green transition would involve substantially more jobs than those that will be lost as the fossil fuel economy ends.

Beuret’s pessimism over jobs is also related to pessimism about the way in which the production of solar, wind and other green technologies will take place. It is certainly the case that production is currently dominated by China and he assumes that this will inevitably continue. As a result, he believes that new jobs in the Global North will be exclusively concerned with installing technology produced elsewhere – what he calls the installation economy. Surely there’s a strong case for sites of production to be closer to where equipment will be used to minimise transport distances.

Blockade and refusal

The second half of the book discusses what is to be done. To date the climate movement has largely attempted to persuade states to see the logic of what needs to be done and take action. Beuret argues that there needs to be a much more confrontational approach. He notes that:

The fossil economy is produced in specific places. If we are to build the kind of disruptive power that can move us towards the rapid ending of fossil fuels, then it is precisely at these critical junctions that we must organise.

He characterises the direct action taken by Extinction Rebellion, Just Stop Oil and others as propaganda. He notes that this kind of direct action can win victories through raising consciousness and pressurising politicians. However, to win the kind of systemic change required to break fossil capital he argues that direct action in the form of the blockade is necessary. An effective blockade has to be long term, sustained and targeted at choke points in the fossil fuel supply chain. Most of all it needs to materially affect the operation of the production or the supply chain that is being targeted. It requires organisation and development of cadres. He notes that contemporary examples of the blockade are rare. In Britain in the 1990s direct action stopped the introduction of GMO crops and Thatcher’s huge programme of road building that began in 1989 was severely limited by persistent blockading through permanent encampments. Roughly ten years later in Australia the development of the Jabiluka Uranium mine was stopped by 5,000 protestors camped close to the proposed site.

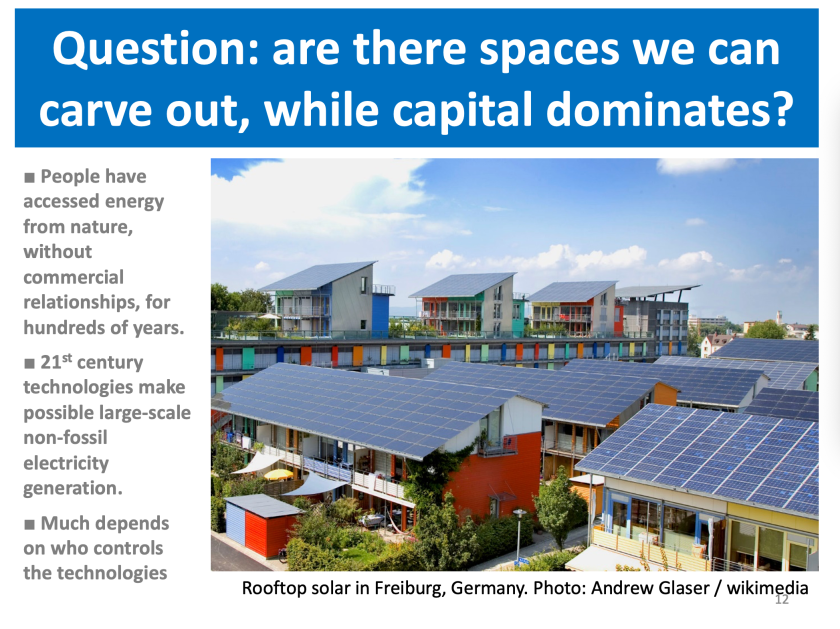

Having introduced the blockade, the discussion moves on to other forms of direct action. There’s an important emphasis on building on the anger of working-class people faced with paying the price of transition and a sympathetic use of the French Gilets Jaunes as an example of how this might be developed. There’s an interesting discussion of past examples of community-based campaigning such as the Anti-Poll Tax campaign, tenant organising and actions over transport costs. The emphasis is on developing popular campaigns of refusal. In Beuret’s view, deep community organising includes activity in communities and in the workplace. Workplace organising needs to include fighting around issues of social reproduction and wider political and community issues need to be taken into the workplace. The task is not simply to reject and disrupt the transition but to simultaneously build our own transition from below. In all this there is a rejection of asking governments to act – in effect the mainstream approach of the climate movement for so long.

I want to insist that although it has problems, Or Something Worse is well worth reading. At a time when the left is struggling to be relevant in the face of existential crisis and a burgeoning far right, books like this are essential. They help develop ideas about how to catalyse, grow and coalesce resistance at the level that is required to shift the momentum towards self-conscious collective working class led action locally and internationally.

Or Something Worse by Nicholas Beuret is published by Verso Books.