A few days ago we published Scot.E3’s Briefing #10 on Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS). In the briefing we take a critical view of BECCS. A newly published book by Holly Jean Buck – ‘After Geoengineering’ (Verso 2019) takes a more positive view. As a contribution to the debate on this important issue we republish (with permission) a detailed review and critique of ‘After Geoengineering’ from the PeopleandNature blog. The review concludes by noting that

The best way to challenge corporations and governments is to make this discussion our own, rather than their property. Then we will be better armed in battles over political choices that we hope not only to influence, but to take into our hands.

Geoengineering: let’s not get it back to front

We need to talk about geoengineering. Badly. To do so, I suggest two ground rules.

First, when we imagine futures with geoengineering, whether utopian or dystopian, let’s talk about the path from the present to those futures.

Second, if society is to protect itself from dangerous global warming, it will most likely combine a whole range of different methods; there is no silver bullet. So we need to discuss geoengineering together with other actions and technologies, not in isolation.

In After Geoengineering, Holly Buck urges social movements and climate justice militants to engage with geoengineering, rather than rejecting it. She questions campaigners’ focus on mitigation, i.e. on measures such as energy conservation and renewable electricity generation that reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Civil society groups protesting at the UN climate talks in Lima, Peru, in 2014, when fossil fuel companies organised sessions on carbon capture and storage. Photo by Carol Linnitt from the DeSmog Blog.

Buck offers a clear, jargon-free review of technologies, from afforestation and biochar that some climate campaigners embrace, to solar radiation management, the last word in technofixes that is broadly reviled. She intersperses her narrative with fictional passages, warning of the pitfalls of “mathematical pathways or scenarios, behind which are traditions of men gaming our possible futures” (p. 48).

But one of Buck’s key arguments – that we will reach a point where society will collectively “lose hope in the capacity of current emissions-reduction measures to avert climate upheaval”, and “decide that something else must be tried” (pp. 1-2) – cuts right across both my ground rules.

Buck asks: are we at the point […] where “the counterfactual scenario is extreme climate suffering” and therefore “it is worth talking about more radical or extreme measures [than mitigation]”, such as geoengineering? “Deciding where the shift – the moment of reckoning, the desperation point – lies is a difficult task” (p. 4).

This is a false premise, in my view, for three reasons.

First: we can not, and will not for the foreseeable future, perceive this “desperation point” as a moment in time. For island nations whose territory is being submerged, for indigenous peoples in the wildfire-ravaged Amazon, for victims of hurricanes and crop failures, the point of “extreme climate suffering” has already passed. For millions in south Asian nations facing severe flooding, it is hovering very close. For others living on higher ground, particularly in the global north, it may not arrive for years, perhaps even decades. If we take action, it will hopefully never arrive in its more extreme forms. This slow-burning quality of climate crisis is one of the things that makes it hard to deal with.

Second: at no point in the near future will “we” easily be able to take decisions on geoengineering – particularly the large-scale techniques – collectively. Political fights over geoengineering are pitting those with power and wealth against the common interest, and it’s hard to see how it could be otherwise.

Buck writes: “There will be a moment where ‘we’, in some kind of implied community, decide that something else [other than mitigation] must be tried” (p. 2). But she doesn’t probe who this “we” is, or spell out the implications of the fact that, in the class society in which we live, power is appropriated from the “implied community” by the state, acting in capital’s interests.

We can only decide, to the extent that we challenge their power. We can not free technologies from that context without freeing ourselves from it.

Third: the political fights actually unfolding are not about “geoengineering vs extreme climate suffering”, but about “geoengineering vs measures to cut greenhouse gas emissions”.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is lauded by the fossil fuel industry as an alternative to cutting fossil fuel use; Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) is included in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) scenarios in order to cover up governments’ failure to reduce emissions; research funds that go to technofixes such as ocean fertilisation and solar radiation management (SRM), that sit easily with centralised state action, do not go to decentralised technologies that have democratic potential.

Buck believes that, despite these current clashes, we can uncover ways of using geoengineering for the common good. For example, she writes of expensive and unproven techniques for direct removal of carbon from the atmosphere:

We have to move from reflexive opposition of new technologies toward shaping them in line with our demands and alternative visions (p. 206).

Shape technologies in line with our visions of a socially just society? Yes, certainly. Start with direct carbon removal or CCS? Absolutely not.

We should focus, first, on technologies that produce non-fossil energy, and those that cut fossil fuel use in first-world economies and the energy-intensive material suppliers in the global south that feed them. We need also to understand technologies of adaptation to a warmed-up world (e.g. flood defences and how they can work for everyone, and not just the rich).

On the global climate strike, 20 September, in London

As for technologies that suck carbon from the atmosphere, if they can be used in the common interest at all, it should be a matter of principle that “soft” local technologies (e.g. afforestation and biochar) be researched and discussed in preference to big interventionist technologies like SRM.

I will expand these arguments with reference to three themes: (1) the current treatment of geoengineering techniques by governments and companies; (2) whether, and why, we should start with “soft” and local technologies, as opposed to big ones; and (3) how we might compare geoengineering with mitigation technologies.

Geoengineering, states and companies

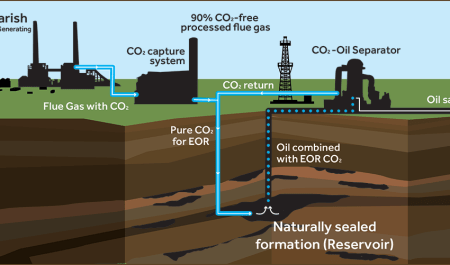

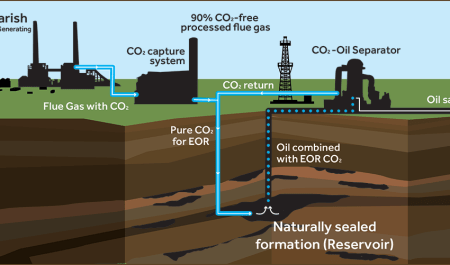

The dangers inherent in Buck’s approach are nowhere clearer than with CCS. This technique extracts carbon dioxide from wherever it is emitted, e.g. power stations’ smokestacks, with “scrubbers” (often using adsorbent chemicals). The CO2 is then trapped, liquefied and transported to a site nearby to be stored.

CCS was developed by oil companies more than 40 years ago in the USA, as a technique for Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR), i.e. squeezing extra barrels of oil out of a depleting reservoir. The captured carbon is pumped into oil reservoirs to increase the pressure, and increase the volume of oil that could be pumped to the surface.

More recently, CCS has been used to trap carbon dioxide emissions at power stations and other industrial sites. But it is so complex, and so expensive, that its supporters say it can not yet be applied at large scale. It has never lived up to decades of talk about its potential.

Buck, displaying a super-optimism that strains credibility, writes:

Perhaps industry’s failure to make use of this technology could even be an opportunity to redirect it for more progressive ends (p. 124).

Linking it with biofuel production is “an opportunity to appropriate this group of techniques for redistributive ends” – which would require “an appetite for paying for and living with expensive infrastructure – and for making bright, clear distinctions regarding how and why it is built” (p. 127).

Who will steer the introduction of geoengineering techniques? Buck argues that:

If there’s no progressive vision about how to use CCS, […] the oil companies can essentially take us hostage (p. 203).

To advance an alternative vision to the companies’ would require a price on carbon, she argues (p. 204); a discussion about nationalising oil companies (p. 206); and a movement to demand carbon removal from the state, linking it to an end to subsidies for fossil fuels (p. 207).

This logic is back-to-front.

CCS, unlike renewable electricity generation and a string of proven mitigation technologies, will require years of development before it can work at large scale and in a manner that makes any economic sense.

Moreover, CCS’s function is to remove carbon dioxide already produced by economic activity.

So in every situation, the first question to ask about it is: is there not a way to avoid emitting the carbon dioxide in the first place?

Let’s imagine an optimistic scenario, in which, in a western oil producing country, e.g. the USA or UK, a social democratic or left-leaning government, committed to serious action on climate change, is elected. The oil companies find themselves fighting a desperate battle to protect their practices and profits; a progressive, working-class movement seeks to control and contain them.

That movement will surely put stopping fossil fuel subsidies at the top of its list of demands. Some sections of it might demand carbon taxes (and some oil companies are already reconciled to these). At best, some of the oil companies will be nationalised.

But then we will surely face struggle over what to do with the funds freed up by an end to subsidies, and what to do with companies over which the state has taken control. Should funds be invested in CCS development? Or in proven technologies that can slash fossil fuel demand? Should oil companies be directed to use their engineering capacity to develop CCS? Or to use it to complete the decarbonisation of electricity generation and start working on other economic sectors?

Carbon Capture and Storage with Enhanced Oil Recovery. From the Power Engineering International web site

If there is a situation where CCS research would be preferred, I can not imagine it. And Buck didn’t spell one out in her book.

One difficulty I had with Buck’s argument is that in a crucial section on CCS (pp. 133-137), she discusses it together with direct capture of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, a different technique (also currently too expensive to be operable at any scale). Her interest in the latter relates to a possible future need to draw carbon dioxide down from the atmosphere more rapidly than can be done with other “softer” technologies (biochar, afforestation, etc).

This is something we might have to worry about in many years’ time, and I don’t want to speculate about it now.

If there is a situation where CCS research would be preferred, I can not imagine it. And Buck didn’t spell one out in her book.

One difficulty I had with Buck’s argument is that in a crucial section on CCS (pp. 133-137), she discusses it together with direct capture of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, a different technique (also currently too expensive to be operable at any scale). Her interest in the latter relates to a possible future need to draw carbon dioxide down from the atmosphere more rapidly than can be done with other “softer” technologies (biochar, afforestation, etc).

This is something we might have to worry about in many years’ time, and I don’t want to speculate about it now.

But Buck sees both technologies as a way of reforming oil companies, in the course of implementing a Green New Deal in the USA, i.e. as a current political issue. Direct air capture could “breach the psychic chain between CCS and fossil fuels”, she suggests (p. 127).

Now? Or in many years’ time? After our movement has grown strong enough to stop fossil fuel subsidies, or even to nationalise oil companies? Or before? Timing and sequencing matter.

Given that CCS and direct air capture are both monstrously expensive and many never work at scale, and given the emergency nature of climate action, proven mitigation and renewable electricity generation technologies should be our priority. That’s the quickest way of reducing the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. If that doesn’t fit with oil companies as presently constituted, tough on them.

The other potential use of CCS that Buck discusses is in conjunction with bioenergy (BECCS). CCS with fossil-fueled processes only saves the carbon those processes have produced, and is at best carbon-neutral. BECCS is seen as potentially carbon-negative, i.e. it could leave the atmosphere with less carbon than it started with. Plants naturally capture carbon as they grow; if they are used for fuel, with CCS, that carbon is also captured and stored.

BECCS is unproven to work at scale, in part because it would need massive amounts of land to grow the crops, presenting a potential threat to hundreds of millions of people who live by farming.

The principal practical use of BECCS so far has been by the IPCC: by including wildly exaggerated estimates of BECCS use, they have made their scenarios for avoiding dangerous climate change add up, without too rapid a transition away from fossil fuels.

This use – or rather, misuse – of BECCS has provoked outrage from climate scientists since the IPCC’s fifth assessment report was published in 2014. (See e.g. here.)

One team of climate scientists who double-checked the calculations, led by Sabine Fuss at the Mercator Research Institute in Berlin, concluded that the IPCC projections of BECCS’s potential was probably between twice and four times what is physically possible.

The best estimates Fuss and her colleagues could make for the sustainable global potential of negative emission technologies were: 0.5-3.6 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide removal per year (GtCO2/yr) for afforestation and reforestation, 0.5-5 GtCO2/yr for BECCS, 0.5-2 GtCO2/yr for biochar, 2-4 GtCO2/yr for enhanced weathering, 0.5-5 GtCO2/yr for direct air capture of carbon and 0-5 GtCO2/yr for soil carbon squestration.

Fuss and her colleagues wrote that they share “the widespread concern that reaching annual deployment scales of 10-20 GtCO2/yr via BECCS at the end of the 21st century, as is the case in many [IPCC] scenarios, is not possible without severe adverse side effects.”

And that’s putting it in polite, scholarly language.

Buck does not discuss this dispute, perhaps the sharpest public rift between the IPCC and the climate scientists on whose work it relies. She only comments in passing that, to answer why the concept of BECCS has any life in it, “possible answers include” that “modelers needed a fix for the models, and BECCS seemed the most plausible” (p. 64). That’s wildly understated.

Further on, Buck speculates that “deployment [of BECCS] at climate-significant scales would be a massive feat of social engineering”, which would imply “a different politics” under which people who live on and work the land own the resources for production (pp. 68-69).

Again, this argument is back-to-front.

I embrace the idea of speculating about a post-capitalist future in which industrial agriculture, along with other monstrosities, has been overcome. And I would not exclude the idea that BECCS in some form might be part of it. But long before we get to that stage, there is the current battle to be fought: we need to join with the many honest climate scientists who have denounced the fraudulent use of BECCS in the IPCC’s scenarios; to expose its use as a cover for pro-fossil-fuel government policies; and address the climate policy priorities those governments seek to avoid. Now, BECCS is not one of these.

Big and small, “hard” and “soft”

The geoengineering technologies discussed by Buck range from those that are by their nature local, small-scale and “soft”, to the largest, “hardest” technologies such as SRM. At the furthest “soft” end is biochar, a process by which biomass (crop residues, grass, and so on) is combusted at low temperatures (pyrolysis) to make charcoal, which can be mixed into soils or buried, to store the carbon. Afforestation is also on the “soft” end of the scale, as are some ocean farming techniques. Buck also points to some significant local, if not “soft”, techniques, such as engineering specific glaciers to prevent them from melting (pp. 247-248).

Direct Air Capture, used with Enhanced Oil Recovery. Cartoon from the GeoEngineering monitor web site

Buck is sceptical of some claims made for the potential of afforestation, and I am too. But her appeals to social movements to engage, instead, with big and “hard” technologies left me unconvinced.

“The shortcomings of large infrastructure projects have generated suspicion about megaprojects, suspicion which may be transferred to solar geoengineering” (p. 45), she writes. Quite rightly so, I say.

Degrowth advocates, Buck complains, believe that “technologically complex systems beget technocratic elites: fossil fuels and nuclear power are dangerous because sophisticated technological systems managed by bureaucrats will gradually become less democratic and egalitarian” (p. 160). The belief that big technological systems “result in a society divided into experts and users […] limits the engagement of degrowth thinking with many forms of carbon removal, which is unfortunate” (p. 161).

What about the substantial issue? Don’t sophisticated technological systems managed by bureaucrats really become less democratic and egalitarian? Aren’t the degrowth advocates right about that? Hasn’t nuclear power, for example, shown us that?

Arguments similar to Buck’s about geoengineering techniques – that, if they were controlled differently, could be of collective benefit, and so on – have long been made about nuclear power, the second largest source of near-zero-carbon electricity after hydro power. But experience shows that nuclear’s scale has made it intrinsically anti-collective: in our hierarchical society, it has only been, and could only have been, developed by the state and large corporations. From where I am standing, SRM and CCS look much the same.

Take another technology that is in a sense both big and small: the internet. Its pioneers saw its huge democratic potential as a tool of communication, but as it has grown, under corporate and state control, it has become an instrument of state surveillance, corporate control and mind-bending marketing techniques.

For Buck, the internet of the early 2000s was “new and transformative, before we knew it would give us so many cat videos and listicles and trolls”. She appeals to critics of geoengineering, who “tend to locate the psychological roots of climate engineering in postwar, big science techno-optimism”, to think of it instead as “a phenomenon born of the early 2000s, a more globalist moment” (p. 44).

I do not recognise, in the early 2000s, this moment of hope for the internet or for “globalism”. The terrorist attack on the USA on 11 September 2001 marked the end of a desperate game of catch-up, played by US regulatory agencies against the Silicon Valley entrepreneurs: it prompted demands by the security agencies that the state’s focus shift from stopping the tech giants hoovering up information, to insisting they share that information with the state.

The Boundary Dam carbon capture project in Saskatchewen, Canada, one of the small number of existing CCS projects

All restraints on the invasion of personal privacy were removed. In China, the state is now combining the same technologies with facial recognition software to take control over citizens to a new level. (Shoshana Zuboff writes about this in her book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.)

A range of socialist writers from Andre Gorz onwards have theorised the way that technology is shaped by capitalism and can not be seen as inherently progressive. A new generation of technological determinists such as Alex Williams and Nick Srnicek, and Leigh Phillips, have offered a challenge to this tradition (which has left me completely unconvinced).

A serious discussion of geoengineering will necessarily be contextualised by consideration of these underlying issues about technology.

To my mind, socialist and collectivist politics can embrace “soft” and small technologies more easily than large ones, because they can more easily be used independently of structures of power and wealth. In many cases, e.g. electricity networks, we may well find ourselves advocating a combination of big and small technologies. But if we envisage socialism as a process that resists and eventually supercedes the state and big corporations, then in principle those technologies that can only be mobilised by the state and big corporations, such as nuclear power – and the big “hard” forms of geoengineering – present greater problems to us.

Which technologies? That’s a political battle

Buck argues that “a world patterned around carbon removal would be similar to one that’s committed itself to deep decarbonisation and extreme mitigation”, but had gone one step further. On the other hand, she writes that “regeneration, removal, restoration and so forth [her descriptive categories for a range of geoengineering techniques] bring a different narrative than mitigation, and perhaps a different politics”. It might be easier to “build a broader coalition around regeneration”, although, or perhaps because, “the goal is more drastic” (p 192).

To point to geoengineering advocacy as an alternative, preferable to mitigation (i.e. reduction of carbon emissions), carries a great danger of playing into the hands of corporate and government opponents of action.

Who, in the here and now, will comprise this “broader coalition” to consider geoengineering? According to Noah Deich of Carbon 180, who is quoted by Buck (p. 246):

[T]here’s the global Paris Agreement community [?], as well as energy, mining and agriculture, all of whom need to embrace carbon removal, ‘not as a scary transformation for their business, but really the natural evolution for where they need to go to increase prosperity. To serve their customers, employees, shareholders, all of these key stakeholders better. It needs to come from the top down.’

This version of geoengineering advocacy, which seeks to combine it with satisfying corporate needs to “serve stakeholders better”, scares me stiff. How can it be anything but craven greenwash?

Buck is not herself advocating such alliances. But she clearly sides with big and “hard” technologies against small, “soft” ones.

She derides supporters of regenerative agriculture for their “determined post-truth faith in soils”, which, she fears, “could contribute to a failure to invest in other technologies that are also needed for this gargantuan carbon removal challenge” (p. 116).

Why send more funds the way of big technologies? Already, “eco-system based approaches”, including afforestation and regenerative agriculture, only get 2.5% of global climate finance, Buck has reported a few pages earlier (p. 96).

Soft” afforestation and biochar, or “hard” CCS and SRM? Buck cites a research group headed by Detlef van Vuuren of Utrecht university in the Netherlands, who proposed that the 1.5 degrees C target could be met with minimal amounts of BECCS and other types of carbon dioxide removal. (Reported here; full article (restricted access) here.) They propose a larger programme of afforestation, and more rapid expansion of renewables-generated electricity, than in the IPCC scenarios. Van Vuuren and his colleagues also factor in lifestyle changes, including an overhaul of food processing towards lab-grown meat.

Buck is sceptical about the prospect of this “dramatic transformation”, as opposed to a focus on carbon removal – although she concludes that it should be “a vibrant matter of debate” (p. 109). And I agree with her there. But still more important is a related debate that is absent from her book: the potential of energy conservation, rather than carbon removal, in the fight against dangerous climate change, which has been downplayed in the IPCC’s reports for years.

By energy conservation I mean the overhaul of the big technological systems that wolf down fossil-fuel-produced energy. This involves other dramatic transformations: of industrial, transport and agricultural practices, and in the way people live – particularly in the cities of the global north where transport systems are based on cars (or, now, SUVs), people are encouraged to consume some goods (e.g. hamburgers) unhealthily and excessively, and live in heat-leaking, energy-inefficient buildings.

These transformations could not only forestall dangerous climate change, but also make lives better and more fulfilling.

An indication of energy conservation potential is provided by a group of energy specialists, headed by Arnalf Grubler of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria, who last year published a scenario suggesting that the 1.5 degree target, along with sustainable development goals, could be met entirely by energy conservation.

The point is not that one of these groups of technology researchers is 100% right as against another group. Rather, that to inform a serious discussion on these issues among people who are concerned about social justice and climate justice, we need to consider the relative advantages and disadvantages not only of different types of geoengineering, but of energy conservation measures too.

The best way to challenge corporations and governments is to make this discussion our own, rather than their property. Then we will be better armed in battles over political choices that we hope not only to influence, but to take into our hands. GL, 1 November 2019.