Between two and three thousand marched in Glasgow on 15 November

Photos from Scotland’s climate march

Between two and three thousand marched in Glasgow on 15 November

Adam Greenfield argues that the key battles over climate are lost and activists should focus on adapting to the results of that failure. Pete Cannell responds that the only possible choice is to keep fighting for social change.

A version of this review was first published on the rs21 website.

In October 2012 hurricane Sandy wrought havoc on the eastern seaboard of the US. The storm surge overwhelmed New York’s sea defences and destroyed the homes and livelihoods of many thousands of working-class New Yorkers. The response of the city authorities was slow and totally inadequate. In its place, networks built a year earlier through Occupy Wall Street stepped in to mount a huge programme of mutual aid which became known as Occupy Sandy. Adam Greenfield, the author of Lifehouse, was one of the volunteers.

2024 was the first year that global average temperatures exceeded pre-industrial levels by 1.5°. Each year since 2022, global average temperatures have increased at an unprecedented rate. Year on year, global heating is matching the most extreme end of the range of possibilities predicted by climate scientists. And, while energy generated from solar and wind power increases apace, fossil fuel use is at an all-time high and greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise. Even if there were a massive shift to a low carbon economy tomorrow, rising temperatures, extreme weather and rising sea levels are baked into the global system for decades, probably centuries, to come.

In his new book Lifehouse: Taking Care of Ourselves in a World on Fire Greenfield responds to this scenario by arguing that attempts to mitigate climate change have failed. He makes three assumptions:

that a so-called ‘green energy transition’ will not take place in time to prevent the most consequential drivers of change from happening; that reparative ’geoengineering’ will not be attempted at the necessary scale or, if attempted, will not work as intended; and that in the time available to us, we will not invent some other technology capable of siphoning carbon from the atmosphere at the necessary scale, and rescuing ourselves that way.

Considering this, he calls on activists to redirect their efforts to adapting to the inevitable consequences of that failure. The core of the book draws on his experience of Occupy Sandy, the ideas of social theorist Murray Bookchin and other examples of collective social organisation including the Black Panthers and Rojava.

The climate movement has always included activists who have argued for a return to nature, a retreat to a rural life that would involve rejecting all aspects of modernity. Greenfield’s position is different. He recognises that most of the world’s population live in big urban centres and will likely continue to do so. Building on his Occupy Sandy experience he suggests that every area needs to develop a Lifehouse, a building or complex of buildings that would form a focus for mutual aid, care and support for the local community – a place to meet and organise, find and share skills, grow food, provide medical services and much more. In any given urban area there would be many such sites.

Greenfield expects that the deepening impact of the climate crisis will have a disrupting effect on the operation of the complex interconnected system that is 21st century capitalism. This is certainly true. He also assumes that the retreat from state provision of public services that has developed in the neo-liberal era will continue. He argues that:

if the state withdraws from [the provision of public goods] then there is only one possible response, which is for populations to self-organize to provide their own commons.

Accepting this, Greenfield then pays little attention to the state as he develops the Lifehouse concept. I think this a profound mistake for reasons which I will attempt to address in the rest of this review.

Greenfield’s articulation of Bookchin’s ideas recognises real problems with the Lighthouse model. He notes that local systems of mutual aid may well be predicated on exclusivity, racist or misogynist ideas. Clearly the survivalist movement in the US is an example of this. And in response to the cost-of-living crisis in Britain the far right was, and remains, proactive in setting up food banks and spaces where people could seek support. His response is to suggest that the Lifehouse model should include an assumption of connectedness or confederation with other Lifehouses. He also notes that Lifehouses are likely to attract hostile responses from the state or from non-state reactionary forces. Again, I think this is right. While states welcome some forms of substitution for welfare services – typically charity run food banks and other services – they are much less keen on initiatives that involve collective working-class organisation.

The Lifehouse model assumes explicitly that it is possible to organise outside the state and alongside the state. Greenfield argues that we should start building Lifehouses now. But almost everywhere that brings you up against a state that is increasingly repressive and intolerant of dissent, in a context of militarism, racism, misogyny and transphobia and the growth of the far right. If we forswear mitigation and throw all our energies into adaptation it seems to me that we are in effect surrendering the ground to reaction. Greenfield notes at one point that a dystopian future might yet include small, favoured patches of relative normality, refuges for the rich. We can be sure that such enclaves would be armed to the teeth. On the other hand, if we focus on adaptation and turn to building Lifehouses our small patches of mutual aid and cooperation would have no such defence.

I want to argue that the alternative is to take system change seriously. That means breaking and replacing the capitalist system. I’m conscious that here and now that might seem as utopian as the idea that we can remodel the world as a connected web of confederated Lifehouses. I’m open to the idea that a sustainable world might look something like Adam Greenfield’s vision. But the key challenge is surely how we can turn the world upside down and end the system which is driving us to disaster? And here socialists have a historic responsibility.

It’s clear that the climate crisis is systemic. The capitalist system has driven huge increases in material wealth through the exploitation of human labour and through commodification of the environment and material world. The system depends on continual growth and is incompatible with sustainable existence on a finite world. Revolutionary socialists have always argued that if those who labour seize the means of production, the fruits of human labour could be shared equally. We talk about a world to win that could provide comfort, leisure and security for all. Today, however, the world we inherit is one where, as a result of the environmental damage caused by two centuries of industrial capitalism, the conditions of human existence are far more inhospitable than was the case previously. The socialist revolution would necessarily apply the emergency brake to runaway climate change, but it can’t stop the damage that has already been done. The conditions for human existence in a world without capitalism will present a challenge for survival. Many of the world’s major cities will be underwater, there will be mass migration as some areas become too hot for human habitation and food production will be under huge strain in a world where extreme weather events are far more frequent.

Socialists can’t promise a future of what has been called ‘fully automated luxury communism’. But we can expose the lies and deceptions of mainstream bourgeois governments and the far-right populists who are jockeying to replace them with the promise of a return to some earlier and mythical time of comfort and security. No such promise is possible in a world on fire. Of course, exposing the lies is only possible if there are demonstrably possible alternatives and that’s our task to develop and popularise.

The wealth of the capitalist ruling class is built on the labour of generations of workers around the world and the blood and bones of the untold millions who were murdered through war and colonisation as capitalism spread around the globe. It is a system of great power and sometimes open, sometimes concealed, brutality. However, it depends for its existence on a global working class. Moreover, in this era of late capitalism it depends critically on complex systems and long global supply chains that can break if key workers withdraw their labour or under the impact of extreme weather events. It’s brittle and vulnerable. That’s why Adam Greenfield’s argument for giving up on mitigation is so wrong.

Winning political arguments about who’s to blame for the crisis and how to ensure a secure future for all is not easy. In hard times it’s necessary for the left to articulate ‘freedom dreams’. Part of the argument has to be about a new economy that provides that security. But it also needs explicit recognition that the system that puts profit before the lives of people and trashes the life chances of future generations has to end. Achieving that goal requires a compelling vision and building collective power in workplaces and communities around the world. Along the way some states may be forced to make concessions and take mitigating action – but the only sustainable end game is the overthrow of those states.

This critique of Lifehouse is not an attack on mutual aid. Practices of mutual aid are a vital and necessary part of working-class resistance – most notably in the urban centres of the global south. At times they may be essential to sustain class struggle and community survival but always against the state. To build sustainable centres for collective support and organisation requires the development of networks of resistance built through class struggle. And if we do that then we can aspire to so much more.

Lifehouse: Taking Care of Ourselves in a World on Fire

Adam Greenfield

Join the Friends of St Fittick’s Park for a demonstration to protect St Fittick’s Park in Torry from industrialisation.

Join the Friends of St Fittick’s Park for a demonstration to protect St Fittick’s Park in Torry from industrialisation.

The last remaining greenspace in Torry is under threat from a bogus “Energy Transition Zone” factory.

Aberdeen City Council are deciding on a planning permission in principle application that will deprive the wildlife in the park and the people of Torry, our much-loved environmental haven.

Come along to tell the council they’re nae getting awa wi it this time! They must reject the ETZ application.

We invite everyone to wear blue to create a wave of people and to show the flood waters in St Fittick’s Park are rising, a key reason why the application should be rejected.

Watery-related props are welcomed.

Meet at Marischal College, Broad St, Aberdeen, 7 Nov. at 9 am before we ‘flow’ over to the Town House.

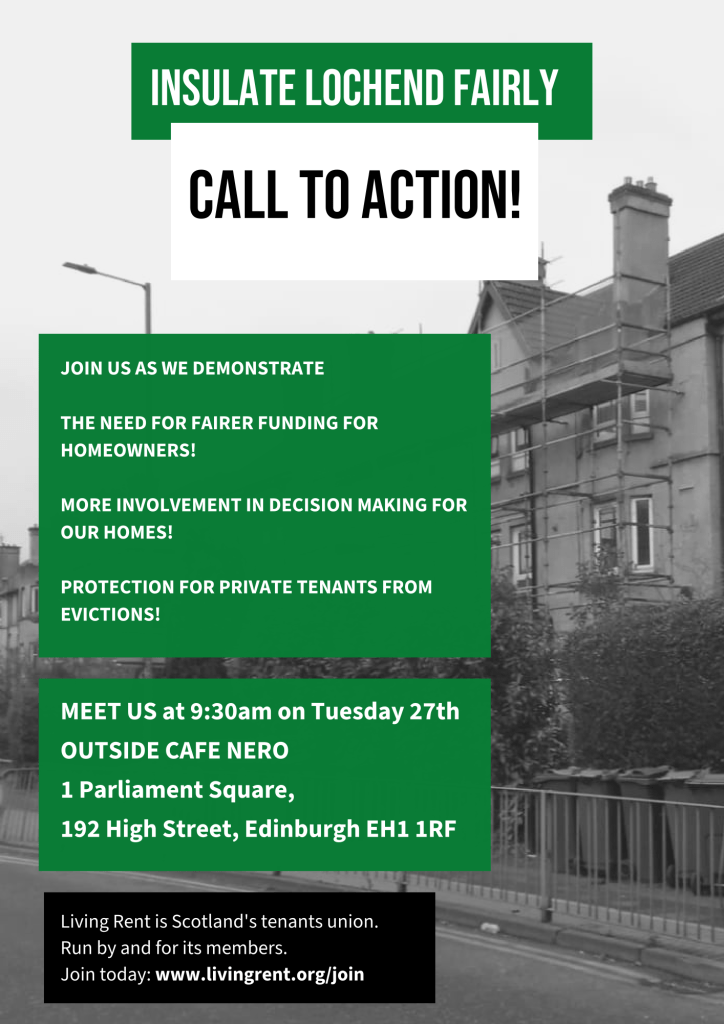

From Living Rent

SUPPORT LOCHEND RESIDENTS DEMANDING FAIR RETROFITS: PROTEST AT EDINBURGH CITY CHAMBERS

Edinburgh City Chambers 10am Tuesday 27th August. (Meet outside Cafe Nero from 9:30)

Lochend is in the midst of a Council-led repair and retrofit project (“MTIS”) covering more than 400 homes, work that’s desperately needed to address years of neglect, reduce fuel poverty and climate-proof our community. But the Council’s plan leaves working class flat owners facing vast invoices, private tenants risking eviction, and social tenants missing out too when their neighbours can’t afford to pay.

In one of the most deprived areas of Edinburgh, this is not what climate justice looks like. Members of Lochend Living Rent have been campaigning for a retrofit programme done with us not to us, with enough support to ensure no-one is forced into poverty or out of their home. It’s vital the Council gets this right, now, before it rolls the scheme out to other communities.

Please join us at the City Chambers as we demand a real just transition for Lochend and beyond!

Let us know you’re coming: https://www.livingrent.org/tell_the_council_insulate_lochend_fairly

Read a member’s piece in the Architects’ Journal about the problems with the present scheme: https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/opinion/edinburgh-councils-retrofit-strategy-is-an-orwellian-nightmare

Sign our open letter to the Council: https://www.livingrent.org/insulate_lochend_fairly

On 4 July, the climate-trashing Tory government will be replaced, as good as certainly by Keir Starmer’s “changed” Labour party.

For all its talk of “green prosperity”, Labour plans to work closely with the corporations that profit from North Sea oil and gas and from generating electricity – and who intend to produce, and use, fossil fuels for as long as they can.

Labour’s plans for cutting greenhouse gas emissions from homes and cars are hopelessly timid, because of its conviction that private business does it best.

Under Labour, we will in my view make progress against social injustice and climate change only insofar as social movements and the labour movement:

(i) confront and confound the government, and

(ii) show that action on climate change, far from costing ordinary people money as the extreme right claim, is 100% compatible with combating social inequalities.

In this article I try to identify the likely battlegrounds between our movements and a Starmer-led Labour government:

Fossil fuel production and the path away from it (part 1); electricity generation at national (part 2) and local (part 3) levels; avoiding false technofixes (part 4); and changing the way energy is used in homes and transport (part 5). Part 6 is about bringing these separate, but connected, issues together.

1. Transition away from fossil fuel production on the North Sea

The election-time slanging match about the North Sea’s future has featured politicians’ and union leaders’ cynicism at its worst. In opposition to this, our movement needs serious conversation about how to fight for working people’s livelihoods and run down oil and gas production simultaneously.

The political war of words has focused on Labour’s commitment not to issue new licences to explore for oil and gas in the North Sea.

The Scottish National Party, which fears losing parliamentary seats to Labour, has lashed out with a claim – shown by BBC Verify to be false – that this would cost “100,000 jobs”. This is “a clear about-face” from the SNP, which last year “committed to a built-in bias against granting new licences”, the Politico web site reported.

“Exaggeration and misinformation helps no-one”, given the urgent need for “a clear-eyed conversation about how to ensure that Scottish workers benefit from the transition away from oil and gas”, Tessa Khan of the climate advocacy group Uplift said.

But exaggeration and misinformation is exactly what leaders of the Unite union, which represents many North Sea workers, contributed. They withheld support for Labour’s manifesto, because of its North Sea policy (as well as for much better reasons, such as its employment policies) and endorsed SNP leader John Swinney’s nonsense.

Unite leader Sharon Graham suggests that a ban on oil and gas licences is the main threat to North Sea jobs. That is not true. It usually takes more than ten years from licence issue for a field to start production, so there is only a very indirect connection. In recent years oil corporations’ decisions to slim down their North Sea operations has posed a far more immediate threat.

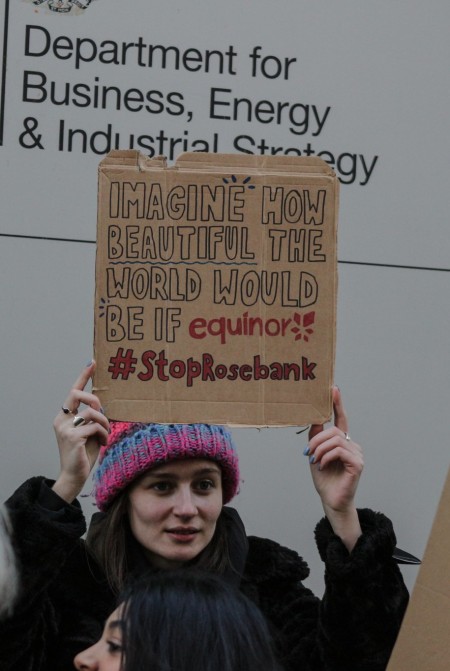

If Labour reverses its ban on new licences, the only beneficiaries will be those corporations – while the planetary disaster threatened by climate change would come one step closer, as the heads of the UN and International Energy Agency have pointed out. Indeed there is a powerful case for scrapping the already-granted licence for the giant Rosebank field.

Unite says it wants to “see the money and the plan” for the transition away from oil and gas. But as its leaders well know, plans already exist.

The Sea Change report, published five years ago, showed how the North Sea workforce could expand, with investment in wind power and other renewables. The oil companies and Tory government have other ideas, set out in the North Sea Transition Deal – which proposes spending £15 billion on their pet technofixes, carbon capture and hydrogen. (See also part 4 below.)

Unite, along with other unions, accepts these false solutions, and calls for investment in hydrogen and carbon capture, as well as wind power.

Perhaps we should be talking about “rupture, rather than transition”, he said, to make gains for social justice and tackling climate change. This starts with uniting oil workers and Scottish working-class communitiesmore broadly. This is the conversation we urgently need.

At a recent gathering of trade unionists concerned with climate policy, Pete Cannell of the campaign group Scot E3 argued that, given the dominance of this technofix narrative, “it’s legitimate to ask whether ‘just transition’ is any longer the right framing”.

2. Public ownership in the electricity system

Labour will set up a “publicly-owned clean power company”, GB Energy, paid for by a windfall tax on oil and gas producers. But GB Energy will own few, if any, electricity generation assets and will focus on partnerships with private capital. Labour also plans to leave the electricity transmission and distribution grids in private hands, and to leave largely unchanged the neoliberal electricity market rules that allowed corporations to reap billions by impoverishing households in the 2022 “energy crisis”.

Labour intends to capitalise GB Energy with £8.3 billion over the next five years: £3.3 billion for a potentially useful Local Power Plan (see part 3 below), and £5 billion to “co-invest in new technologies” including floating offshore wind and hydrogen, and “scale and accelerate mature technologies” including wind, solar and nuclear.

Labour’s loud claim that GB Energy will “lower [electricity] bills because renewables are cheaper than gas” is not credible. This would require, at least, an investment far greater than £5 billion, allied to a root-and-branch overhaul of electricity markets.

More likely, GB Energy will, at best, fund new technologies that financial markets prefer not to risk their own money on – or even follow in the footsteps of Tony Blair’s disastrous Private Finance Initiative, with which corporations milked billions from the NHS. The Guardian, apparently briefed by Keir Starmer’s team, reported that GB Energy will probably start with “investments alongside established private sector companies”, including the chronically over-budget Hinkley Point, Sizewell C and Wylfa nuclear projects.

The Greens and others slammed Starmer, when he finally clarified on 31 May that GB Energy will essentially be an investment vehicle. But a trenchant critique had already been published last year: Unite’s Unplugging Energy Profiteers report, which warned that “unless combined with a public purchasing monopoly, or significant market reform intervention, [GB Energy] will have no impact on distorted pricing in the wholesale market”, and “by concentrating very limited resources on de-risking experimental forms of generation, GB Energy will use public resources to underwrite and further increase future potential profits for the private sector”.

Unite, and the Trades Union Congress, call for public ownership to be extended not only in electricity generation, but also in the supplybusiness and in transmission and distribution networks. Labour madesimilar calls in 2019, but has now ditched them.

Underinvestment in these networks is a scandal as damaging as the water companies’ rip-off: tens of billions of pounds’ worth of network upgrades are needed to facilitate renewable generation and close the gap on missed climate targets.

Already, there are 10+year queues for renewables to be connected to the grid; house-builders are fitting climate-trashing gas boilers because they can not access electricity for heat pumps; battery storage lies unusedbecause companies’ computer systems are out of date … all while distribution networks paid out £3.6 billion in dividends to shareholders in 2017-21.

The system is in such a state that even Rishi Sunak’s dysfunctional government took regulatory powers away from National Grid and put them in the Future System Operator. Nick Winser, the electricity network commissioner, warned the government that unchanged, the system would leave “clean, cheap domestic energy generation standing idle, potentially for years”. “Very few new transmission circuits have been built in the last 30 years”, he said: unless jolted, companies could take up to 14 years to build them.

To make the electricity network fit for the transition away from fossil fuels, wider public ownership is crucial. Our movement needs to work out how to coordinate the fight for it.

3. Community energy and decentralised renewables

Labour promises to spend £3.3 billion on a Local Power Plan, under which GB Energy will “partner with energy companies, local authorities and cooperatives to develop up to 8GW of cheaper, cleaner power by 2030”. Up to 20,000 renewable projects will return “a proportion” of their profits back to communities. But “the detail on these plans is sparse”, the New Statesman reported – and so it is surely up to community organisations and the labour movement to discuss effective ways this money could be spent.

Until now, central government has been a wrecking ball for community energy. In 2015, it changed planning rules, effectively blocking onshore wind projects. In 2019, it scrapped the feed-in tariff paid for electricity supplied to the grid from small-scale renewables. And for years – as decentralised renewables technology leaped forward internationally – it ignored calls to overhaul market rules. Small renewables projects were locked out of the grid by the need for a £1 million + licence, and other obstructions.

The Green New Deal all-party parliamentary group last year called for the regulatory system to be turned upside down, to end its bias in favour of the “big five” generators. It proposed a “European style ‘right of local supply’”; changes to rules on planning and public procurement; mandatory transparency of grid data; and other measures.

Such changes would make it possible to replicate the success of Energy Local in Bethesda, north Wales, which supplies locally-produced hydro power to households at below-grid prices. In April, the Common Wealth think tank proposed a “public-commons partnership” as the institutional form under which local authorities could develop such projects.

All this will take a fight, though. Otherwise, electricity corporates will spread their tentacles into decentralised renewables, as they are doing in the US and Australia.

Furthermore, we need to overcome the official labour movement’s residual reluctance to support community energy projects. The TUC’s recent renewables policy paper, which lists offshore wind, wave, nuclear and “zero carbon hydrogen” (?) as energy technologies – but not decentralised wind and solar – is, unfortunately, indicative.

Decentralised renewables, developed with cooperative, community and local authority forms of ownership and governance, can help to break corporate control of electricity provision, and open the way to democratise and decommodify it.

4. Opposing false technological solutions

False technofixes, including hydrogen and carbon capture, use and storage (CCUS) feature prominently in Labour’s election manifesto – the outcome of lobbying by the oil industry, for which they comprise a survival strategy. Nuclear power – expensive, dangerous, and beloved of the military – is there too, grabbing funds from proven, socially useful technologies such as home insulation, public transport and decentralised renewable power.

While the case against nuclear has been made, and the false logic of CCUS exposed, over decades, the drive for hydrogen is more recent: it is the oil companies’ alternative to electricity-centred decarbonisation. Energy systems researchers argue that, while hydrogen may be needed in future e.g. for steelmaking or energy storage, it will never be suitable for home heating, and hardly ever for transport.

The Tory government has invested heavily in hydrogen, and the 2023 Energy Act provided a framework for its commercial development. But attempts to bribe communities into testing it out for home heating have hit setbacks. A planned test at Whitby, Merseyside, was cancelled last year after vigorous opposition by local residents and the HyNot campaign group. This year a second planned test at Redcar, Yorkshire, and a thirdone in Fife, Scotland, were both postponed.

Catherine Green Watson of HyNot said: “These postponements are great progress for our campaign. But on Merseyside we still have strong local political support for hydrogen in industry, which should not be the priority. Instead, we need to concentrate on upgrading the electricity grid.”

We need a discussion in the labour movement and social movements about the social role of these technologies. We could work towards unity around the principle that they should not receive state funding that could go to quicker, more effective decarbonisation paths.

5. Energy use in our homes and transport

Labour has scaled back its promises to invest in its Warm Homes Plan that will fund grants and low-interest loans for insulating homes and replacing gas boilers with heat pumps. Shadow energy secretary Ed Miliband last year talked about “up to £6 billion a year”; by the time Labour’s manifesto was published last week, this had shrunk to “an additional £6.6 billion over the course of the next parliament” (that is, over five years). Talk of upgrading 19 million homes had stopped; now it’s 5 million.

Labour has stuck with commitments to take railways back into public ownership, and to support municipal ownership and franchising of bus services. But it is also promising to “forge ahead with new roads”, and keep the transport system centred on private cars, at a time when researchers argue that this cuts dangerously across tackling climate change.

If Labour sticks to this course, determined by its neoliberal fiscal rules and by corporate lobbying, then key opportunities to cut UK carbon emissions, while improving people’s lives, will be missed. Researchers have been screaming for years that insulation and heat pumps, and superceding the car-centred transport system with better, cheaper public transport, are desperately needed to decarbonise homes and transport, the two largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions.

Battles on effective energy conservation in homes, transport and throughout the economy are part of the war to limit climate change.

Labour’s commitments are too timid to reverse the disasters caused by Tory policies. In the decade from 2012, annual completions of home insulation upgrades fell by nine tenths. The measures announced by government last year would take 190 years to improve the energy efficiency of the UK housing stock and 300 years to hit the government’s own targets for reducing fuel poverty, National Energy Action stated.

As for roads, the government could cancel the £10 billion Lower Thames Crossing scheme, final approval of which has been delayed until October, and apply to all future projects the principle adopted by the Welsh government – that they can only go ahead if compatible with climate policy.

Labour may not only fail to deal with these gigantic sources of carbon emissions, but actually open up new ones. A grim example is Labour’s threat to overrule communities who question tech corporations who want to build fuel-guzzling data centres – which will help trash climate targets, to the benefit of those corporations alone.

6. Bringing the issues together

The stakes are high. Every new assessment by climate scientists underlines the conclusion reached by leading British researchers four years ago: that the UK’s decarbonisation targets are half as stringent as they need to be, to make a fair contribution to tackling global heating. The government’s own climate change committee says non-power sectors of the economy need to decarbonise four times faster than they are doing.

Tackling climate change, while reversing the effects of 14 years of neoliberal austerity policies, will not be easy. Indeed, Labour does not intend to: both decarbonisation and social policy will be subordinated to their fiscal rules.

The labour movement and social movements need to challenge and push back Labour’s pro-fossil-fuel, pro-austerity approach.

We need to unite our forces and find the pressure points – be it saying “no”, to the Lower Thames Crossing project and similar, or finding openings for collective action, e.g. in the Local Power and Warm Homes plans.

To act effectively on climate, we need to keep in mind the necessity of holistic solutions, and reject illusory technofixes and greenwash narratives that claim to reduce emissions with one hand, and pour them into the atmosphere with the other. SP, 18 June 2024.

This article was first published on the People and Nature site. Republished here with thanks.

Download a PDF version of this briefing

What is the COP?

COP is shorthand for conference of the parties. Organised by the United Nations, it’s normally held on an annual basis, and it is the place where the nations of the world come together to discuss policy on climate action. So, to give it its’ full title COP28 is the 28th annual Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. COP 28 is taking place in Dubai.

A history of failure

The first COP was held in 1995 in Berlin. In terms of making an impact on greenhouse gas emissions the COPs have been an abject failure. The two most common greenhouse gases are carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane. When COP 25 took place in Madrid at the end of 2019 the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere had risen 67 parts per million by volume (ppmv) above the level it was at when the first COP met in Berlin. To put this in perspective CO2 levels increased by more during 25 years of COP discussions than they had in the previous 200 years. Methane levels have tripled since 1995. Greenhouse gases act like an insulating blanket over the earth’s atmosphere and are responsible for rising global temperatures. So, the massive increase in the amount of these gases in the atmosphere is the reason why the climate crisis is now acute and why rapid action to cut emissions is so important.

The Paris Agreement of 2015

Back in 2015 the COP (21) took place on Paris. The conference ended with an agreement that has since been ratified by 189 out of the 197 countries that participated (The Paris Agreement). Ratification committed countries to developing plans that would curtail global temperature rise to less than 2 degrees centigrade. Those who have not ratified include some important oil producers. The USA ratified under Obama but then withdrew under Trump only to return on the first day of Biden’s term of office.

In principle ratifying the Paris Agreement commits countries ‘to put forward their best efforts through “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs) and to strengthen these efforts in the years ahead.’ The reality has been that progress has been negligible. The agreement is essentially voluntary and avoids specific targets. Political economist and environmentalist Patrick Bond notes the ‘Agreement’s lack of ambition, the nonbinding character of emission cuts, the banning of climate-debt (‘polluter pays’) liability claims, the reintroduction of market mechanisms, the failure to keep fossil fuels underground, and the inability to lock down three important sectors for emissions cuts: military, maritime transport and air transport.’

COP fault lines

The COP is dominated by the big powers. So, in the negotiations at every COP there are sharp divisions between the major industrial nations that are responsible for most greenhouse gas emissions and the global south, which endures the biggest impact of climate change. At the COPs, and in the run up to them, there is also a great deal of activity from non-state organisations. Businesses, NGOs and union federations lobby before the event and can obtain credentials that enable them to be within the main conference areas. There is of course a huge imbalance in resources between the corporate lobbyists and the climate campaigners. Groups that represent women, indigenous people and poor people struggle to have their voices heard within the conference. The climate movement is mostly excluded from the conference zone by barricades and police.

COP28

Sultan al-Jaber, the president of COP28 in Dubai is also the director of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company. Before the COP began the BBC disclosed leaked briefing documents showing that meetings with international participants were being used to make new oil and gas deals. Jaber denies that this is the case but in truth it should hardly be a surprise. The Financial Times (FT) describes the COP as a trade fair for the oil and gas industry. Total attendance in Dubai is said to be around 80,000 and dominated by bankers, consultant and lobbyists. These people attend to do business while using PR spin to burnish their climate credentials. The chief executives on the UAE’s COP28 guest list included interim BP chief executive Murray Auchincloss, BlackRock’s Larry Fink, commodity trading group Trafigura’s Jeremy Weir and Brookfield Asset Management’s Connor Teskey. Huge asset management companies like BlackRock and Brookfield are investing in renewables and were involved in the $30bn fund launched in Dubai to invest in climate-related projects – but while total investment in renewables now exceeds investment in fossil fuels the latter has risen year on year for the last four years. There is no sign of fossil fuels being phased out as is necessary to prevent runaway climate change.

Organising for the COP

From the start the COP process has operated within the domain of market economic orthodoxy. It assumes that market forces will drive a move towards less carbon intensive technologies and hence reduce greenhouse gas emissions. There have indeed been significant developments in sustainable technologies – particularly wind and solar. And yet at the same time the big energy companies have pursued a ruthless drive to exploit new hydrocarbon resources in a way that is completely incompatible with even the most modest targets for limiting global warming. Since the COP began global emissions have risen by more than two-thirds.

The history of the COPs has been one of dreadful failure. And yet for many climate NGOs representation and lobbying at the COPs is an annual priority. The COPs are a huge exercise in greenwashing, a jamboree for the corporate decision makers who are very much the problem and not part of the solution. So, yes, we should protest when the COP takes place but there’s a growing movement to say that what we should be doing is boycotting its institutions. There is a real need for international coordination but to get the COP process has failed – we need to break from business as usual. This year as COP28 takes place in air-conditioned luxury in Dubai – Earth Social is organising a grass roots conference in Colombia – check it out at earthsocialconference.org

A message from the organisers of the Earth Social conference – timed to take place in Colombia as COP28 takes place in Dubai.

It boils down to whether we are honest with ourselves, or not.

UN climate summits are a joke that continue to push the bounds of absurdity.

Since they began, yearly global emissions have increased by more than two-thirds. Worse still, no plans have been made to phase out fossil fuels. Should we be surprised when industry lobbyists continue to dominate conferences? Can we expect anything different from this next summit, taking place in a petro-state, chaired by an oil company boss… Are we expected to buy into this charade…?

We, on the other hand, are climate realists. We see where we are being led. We know we need to apply the emergency brake to avoid earth system collapse. That’s why we refuse to participate in a process of trading empty promises any longer.

That’s why we are inviting climate realists to the Earth Social Conference in Casanare, Colombia, from 5th-10th December 2023.

Join us to build the collective force we need in order to pull the emergency break.

Although the conference is in person in Columbia on 7th December it is possible to join some of the sessions by Zoom. Click here to go to the conference website and register.

Yesterday (9th August) campaigners from Climate Camp, This is Rigged and Scot.E3 were outside the office of Environmental Consultants Ironside Farrar in Edinburgh. Ironside Farrar have been commissioned to produce a masterplan as part of the rezoning of St Fitticks Park in Torry into an industrial Energy Transition Zone (ETZ). The protest is part of an ongoing campaign to persuade the workers at Ironside Farrar to direct their skills towards projects that contribute to a socially just transition. Mike Downham spoke at the protest. There will be another protest at the Ironside Farrar office next Wednesday 16th August from 8.30am.

SPEECH OUTSIDE IRONSIDE FARRAR OFFICE 9TH AUGUST 2023

Welcome – and thanks for joining us this morning.I thought I would tell you why we’re here. This is the head office of Environmental Consultants Ironside Farrar – though the door doesn’t say that. We’re here to call on the employees of Ironside Farrar to boycott all further work for ETZ, the company oil tycoon Ian Wood set up to industrialise a large part of St. Fittick’s Park in Torry as an “Energy Transition Zone”. He then commissioned Ironside Farrar to get Planning Permission.

Torry is a suburb of Aberdeen, though it used to be a fishing and boat-building village just across the Dee from Aberdeen City. Then with the discovery of North Sea oil and gas in the 70s most of the village was bulldozed to make space for a Shell oil and gas terminal.

Since then Torry has been dumped time after time with the industrial development that other parts of Aberdeen don’t want – a landfill site, an industrial harbour where the Park used to come down to the beach at Niggs Bay, an incinerator close to the school, and now this threat to the Park which the Torry community cherish as their last green space. The threat to their community is huge. Ian Wood’s money persuaded Aberdeen City Council, who had previously invested much public money in improving the Park, to do a U-turn and re-zone it for industrial development. And Ian Wood’s money persuaded the Scottish Government not to intervene.

Ian Wood says the ETZ will contribute massively to bringing down carbon emissions, but much of the vague talk about what he wants to do is about developing Carbon Capture and Hydrogen technologies both of which are scams. This is in fact an attempt at a land-grab to justify continuing to extract oil and gas from the North Sea and fill the pockets of share-holders and directors in the Oil and Gas Industry.

Torry is about as disadvantaged a community as it gets, with appalling health statistics, appalling air quality and few employment opportunities. Despite this they are rising up and fighting for their lives against this plan to industrialise their Park.

Saving St. Fittick’s Park is exceptionally important, for three reasons:

Two big things have happened in the six weeks since we started this campaign, which make Saving St. Fittick’s Park even more important. Climate has broken down across the world at a speed which wasn’t anticipated. Southern Europe and North Africa are on fire, and unprecedented floods in central China have displaced 100,000 people. The second thing is that the Westminster Government has decided to grant at least 100 new drilling licences in the North Sea. That these things can happen at the same time shows just how strong our governments are committed to fossil capital.

I’ll end by quoting a few things from the booklet The Declaration of Torry, a product of The Torry Peoples Assembly in May: on the back of this booklet they commit themselves to six actions:

And inside the front cover of the booklet, most powerfully:

THIS IS OUR LAND AND NO ONE ELSE’S

THIS LAND BELONGS TO THOSE WHO CARE FOR IT

Just one thing to leave you with. The people arriving for work this morning are highly trained and have knowledge and skills which will be essential when we’ve made the transition to clean energy. They know about tipping points in global heating, and about the complex relationships which underpin biodiversity. Ever since we started this campaign, we’ve been respectful to these workers, seeing them as part of the solution, not part of the problem.

At the same time they must surely understand the enormity of what Ian Wood is planning in Torry. They have the power between them to Save St. Fittick’s Park, by boycotting further work for ETZ. Even if they aren’t in the team working for ETZ, they can bring Ironside Farrar to a standstill by collectively withdrawing their labour.

Glasgow City Council has decided to invest £75,000 in designing a pilot of free public transport, to include buses, trains and the Subway. This decision was a result of more than five years of campaigning by Get Glasgow Moving, strengthened over the last two years by Free Our City, a coalition of climate activists, trade unions and passenger groups.

Representatives of ScotE3, Glasgow Trades Council, Friends of the Earth Scotland, Migrants Organising for Rights and Empowerment, and Govan Community Council, all active members of the Free Our City Coalition, met last week with a Council officer and a representative of Stantec, the large transport consultancy company which won the commission to design a free public transport pilot, whose report to the Council is scheduled for June.

Free public transport, now available in many cities across the world, is vital for reducing Glasgow’s carbon emissions and the many inequalities which plague Glasgow. Get Glasgow Moving had already met separately with Stantec.

Free Our City made these main points to Stantec:

Here’s the REEL News film of the Free Our City demonstration at the Glasgow COP

Our latest briefing takes a critical look at Net Zero. You can read it here or download the PDF. All our briefings are published under a Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0 . Find all our briefings on the resources page.

“Net Zero” was defined at the 2015 Climate Summit in Paris as “a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases”. So, for example, it would be OK to continue burning gas in power stations as long as all the carbon dioxide produced in the process is captured and permanently stored.

Net Zero was an attempt to translate the temperature target of “well under a two degree rise above pre-industrial levels” into something countries could be held accountable for.

Since then governments have rushed to announce long-term Net Zero emissions goals. The Climate Change Committee has also fully embraced the Net Zero concept – hardly surprising because the members of the Committee are appointed by the UK and Devolved Governments.

As a result of these goals billions of dollars have been invested in research and development of low-carbon technologies , all of which face massive technological, economic and land use challenges when used at scale.

The Net Zero concept emerged in 2013 in the run-up to the Paris Summit, against the background of the collapse of the talks at Copenhagen in 2009. However well-intentioned the idea was, it’s notable that it arose among a group of 30 lawyers, diplomats, financiers and activists, who met at Glen House, a country estate in the Scottish Borders owned by a ‘green’ investment pioneer.

The current front runner technology, which governments are pinning their hopes on, is “Carbon Capture with Storage” (CCS). This is defined as “a process in which a relatively pure stream of carbon dioxide (CO2) from industrial and energy-related sources is separated (captured), conditioned, compressed and transported to a storage location for long-term isolation from the atmosphere”. The companies developing this technology are either the same companies which extract fossil fuels, or closely related to them financially.

CCS is an energy-hungry process and as such is not financially viable at scale for the companies experimenting with it. They are calling for government subsidies. In the US extracted carbon dioxide has been used to facilitate pumping in oil wells – a process known as “Enhanced Oil Recovery” – to close the energy gap, make CCS more financially viable, and enable the big energy companies to continue extracting fossil fuels.

On four related counts CCS is not in the interests of either people or the planet. First it requires too much energy; second it would need subsidising by tax-payers; third it would be controlled by giant corporations who already make obscene profits; and fourth it would be too slow to prevent catastrophic climate change.

In the UK at Drax Power Station – the site recently of vigorous strike action by the inadequately paid workers.

– biomass is being burnt and from time to time some of the emitted carbon is being captured in a process called Bioenergy and Carbon Capture (BECCS). A previous ScotE3 Briefing on BECCS explains why this is a crazy idea – primarily because it would require huge areas of land to be planted up with monoculture forests.

It’s clear then that both Net Zero and the technologies which underpin it are meaningless greenwash, being used to justify continued investment in fossil fuel extraction – an effective distraction from the urgent need to deliver sustained radical cuts to greenhouse gas emissions in a socially just way.

What’s needed is a Real Zero, not a Net Zero. We have the technology to achieve this – we don’t need new technology. This is what we need to do: