The “key questions” we hope to discuss today, listed in the agenda, include “how do we cut through with our demands for a clean energy system”, “how do we create the necessary alliances” and “how do we turn the tide of right-wing weaponisation and scapegoating of climate action”.

I will comment on these questions by taking a step back, and considering some underlying issues about how we understand the world – issues that we will come back to again and again, as we are trying to develop political strategies. I hope this is useful.

Some of this will sound general, some of it some of you know better than I do, but my idea is to try to allow us all to consider the basics that underlie all the hard campaigning work.

I will comment on six points: two on politics, two on energy systems, one on technologies, and one on campaigning proposals.

1. To what extent can we talk about UK government “climate policy”? What is the effect of the government’s actions and the way to influence them?

The economic system that we live under has a built-in requirement to expand. Capital needs to accumulate continuously. The government’s function is to facilitate that.

And so the government’s default positions on things that matter in terms of global warming – airports, road building, regulation of the building industry, North Sea oil, and so on – are anchored in its attitude to economic policy (all about “growth”), which serves the needs of capital. Capital, in its drive to expand, undermines and sabotages all climate targets.

We, the movement, must not lose sight of how this works. This is how we end up with the chancellor of the exchequer talking nonsense about electric planes and biofuels, to justify reviving the discredited, climate-trashing Heathrow third runway proposal.

Our understanding of the relationship of capital and the government is obviously relevant to our political strategy.

Take for example the 2008 Climate Change Act, arguably the best bit of legislation we have, under which the UK carbon budgets are set, and which many of us here have used as a political lever for our arguments. Actually it is a double-edged sword. The Act is used by many politicians as a cover behind which to abandon actions that would address climate change.

A starting-point for a critique of the Act is research conducted at the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, and published in 2020, showing that if the UK sticks to its carbon budgets, it pours TWICE AS MUCH greenhouse gas into the atmosphere as it would under a fairly worked-out target.

The Climate Change Committee, supposedly “independent”, has always ducked the crucial question of what proportion of the global carbon budget it thinks the UK could fairly use. It considers what is “feasible”, not what is necessary.[1]

My conclusion from this is NOT that nothing can be done in the political sphere, but that we should recognise how the battlefield is actually set out. Strategies focused on convincing the government, without social movements behind them, will often fail.

2. Do we see the international climate talks as part of the solution, or part of the problem?

In recent years it has become clearer that the oil and gas industry, and governments of fossil fuel producing countries, have to a large extent taken control of the annual conferences of the parties (COPs) through their lobbying machines.

We should not give an inch to the oil companies and their lobbyists. But, in fighting them, we should beware of the idea that the international climate talks set a standard that, without these recent changes, we could return to. That was never the case.

I am talking here about the political agreements made at the talks, not about the scientific research summed up in the reports of the International Panel on Climate Change, that we should all follow as closely as we can.

(When I gave this talk, the very valid point was made in discussion that we can not just “listen to the science”, as some environmentalists say. There is not one “science”: scientific interpretations are also shaped and influenced by social forces and power relations, by the society in which scientists live.)

The international climate agreements were always based on the false premise that there could be green growth. They always combined tolerance for vast subsidies to the fossil fuel industries with the fiction of carbon trading.

And it is not only the climate talks, but all the post-1945 international political institutions, that are in crisis. The weakening of these institutions by Trump, Netanyahu, Putin and others is the outcome of a long process, not the beginning. The outrage of COP talks being run by oil company executives and oil-producing countries’ dictators needs to be seen in this context.

A very real political consequence of all this is that some activists, confronted by the horrific scale of the climate crisis, conclude that the future will inevitably be worse than the present.

These are real fears. And against the background of these fears, e.g. in Extinction Rebellion and organisations that have grown out of it, some people articulate what I call disaster environmentalism, always emphasising the worst possible outcome and minimising our own agency.

This is a very important discussion, and I do not think people active in the labour movement can cut themselves off from it.

We also need to recognise that, as the consequences of climate change become much more visible – floods, wildfires and other disasters – we will see much more civil disobedience by climate activists, and much more state repression in response.

Defending those activists, even those whose methods we might not agree with, is central, in my view.

3. What is our framework for understanding how fossil fuel use can be reduced?

First, let’s question the whole idea of “energy transition”. It has been poisoned, distorted beyond recognition, with misuse by the representatives of capital. In their telling, this “transition” will be led by oil companies, car manufacturing companies, “big tech” and their technofixes.

If you think I am exaggerating, look at the way it was discussed during the prime minister’s visit to Saudi Arabia just before Christmas.

A valuable perspective on this is presented in a new book by the historian Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, More and More and More: an all-consuming history of energy. He shows that previous so-called “energy transition” were actually additions: coal burning did not replace wood burning, but added to it; oil did not replace coal, but added to it.

And certainly right now in China, the world leader in building renewable electricity generation capacity, those renewables are being added to a still-expanding mountain of coal, not replacing it.

A second concept we should question is that “energy” is an undifferentiated thing, bought and sold as a commodity. Energy, like labour, has been commodified over the past several hundred years, by capitalism. But that is not a permanent or natural state of affairs.

Our movement should aspire to the decommodification of energy; we should think of it as a common good that people should have access to by right.

How do we move in that direction? How do we start to disentangle the system that currently delivers energy to people in the form of electricity, heat, or motive power? I suggest we start by considering the technological systems through which fossil fuels are burned and turned into these things that people can use.

I mean technological systems in a very wide sense: not only power stations and electricity networks that burn gas and produce electricity, or petrochemical processing, but also industrial and agricultural systems, urban built environments, transport systems – that all run predominantly on fossil fuels.

These technological systems are embedded in social and economic systems, and stopping fossil fuel use will involve transforming all of these.

Thinking about it in this way, we can identify three ways of reducing fossil fuel use.[2] Starting at the end of the process, where the energy supplies people’s needs, these three ways are:

a. Changing the way that energy is used. For example, replacing car-based transport systems with systems based on public transport and active travel. People do things differently, and better, using far smaller quantities of energy carriers (that is fuels, or electricity or heat, different forms energy takes).

b. Reducing the throughput of energy through technological systems. For example, replacing gas-fired heating with heat pumps run with electricity. The same result is achieved, keeping homes warm, using a small fraction of the fossil fuels burned previously.

c. At the start of the process, replacing fossil fuel inputs with renewable inputs. This is capital’s favourite change, because it does not imply reducing throughput or people living differently. Nevertheless, in my view, we in the labour movement also favour it. For producing electricity and heat, it is quite straightforward. As you know, for other things, such as making steel, it is much trickier.

I suggest this framework because in our campaigning work we are hit with a constant barrage of nonsense about decarbonisation, such as we heard from the chancellor this week about electric planes and biofuels. None of us have to be engineers to answer this stuff, but we need robust analytical categories to work with.

In energy researchers’ jargon, the use to which energy is put at the end of these technological processes – getting from place to place using petrol, heating a room using gas – are called “energy services”. From the 1970s, environmentalists argued that the economy should focus on delivering these services with less energy throughput.

“Energy services” is not a term I would use uncritically. But it’s worth knowing that there are piles of research showing how these energy services can be provided, with a substantially lower throughput of energy carriers.

(Three different, and I think complementary, takes on the UK economy are the Absolute Zero report produced at the University of Cambridge, the Centre for Alternative Technology’s Zero Carbon Britain report and Shifting the Focus, published by the Centre for Research into Energy Demand Solutions.)

4. What do we say about “demand reduction”?

Because mainstream political discourse treats energy as a commodity, it also talks about supply and demand. Actually, demand for energy is a phantom.

No-one wants energy. What people, or companies, want is energy services. These are provided by energy carriers. We want heat, or light, or we want to get from one place to the other. If the technological systems, and the social and economic systems are changed, we can get these same outcomes using far less energy.

Furthermore, energy use is differentiated. The use of energy by a pensioner to keep warm can not be compared to the use of energy at a much greater rate for a company executive to take a plane flight, or a data centre to meet increased electricity demand for crypto currencies or AI.

This should be the starting point for our political strategy. We do not want demand reduction, as our right wing opponents claim. We want to use energy differently, as part of living differently – which is surely what the labour movement has always aspired to, long before the threat of global heating loomed in front of us.

5. How do we understand and respond to technofixes?

Technologies are instruments of labour, used by people in taking from nature their means of subsistence and the material basis of their culture. But those processes go on in specific sets of social relations – for the last three centuries or so, dominated by capital.

Just as labour is shaped and controlled by social forces, so are technologies. So we should beware of thinking of technologies outside of their social context.

An example is the internet. It transformed communication and access to information in ways that have changed all our lives. But we can also see how, in the hands of powerful corporations, it is being used to reinforce the most dangerous changes in society – the growth of dictatorship, the defence of genocide, and deception and lying on an industrial scale. Witness, too, the frightful expansion of energy-intensive data centres, particularly to facilitate cryptocurrency use and AI.

In the energy sector, bad or questionable technologies are supported by capital for its own reasons: those on which attention are currently concentrated are carbon capture and storage, and hydrogen, the primary social functions of which are as survival strategies for oil companies.

Technologies that have the capacity to serve humanity – I am thinking here particularly of solar, including decentralised solar – are distrusted by capital, which seeks to control them.

As a movement, we need to develop our collective understanding of these technologies and our critique of them. A great example has been set by the informal group set up by campaigners and researchers working on CCS.

6. How do we confront the right-wing myths that climate policies are bad for ordinary people?

My conclusion from the last several years of campaigning on climate issues is: to get beyond the small number of people who have thought through the issues, we need to focus firstly on demonstrating the potential of policies that address both global warming on one hand, and social inequality on the other.

This is the way to counter the populist right wing narrative – which has also been taken up by Labour politicians and, on the issue of North Sea oil, even by union leaders – that action on climate change will inevitably hurt ordinary people.

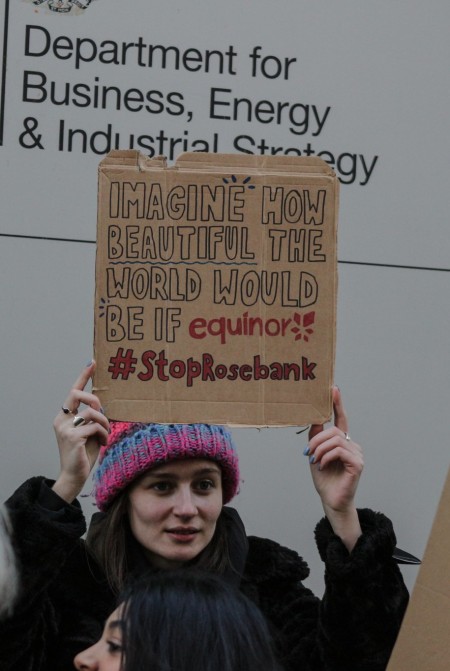

Some exemplary campaigning, looking at how to move away from oil production on the North Sea without repeating the disaster that was visited on coal mining communities in the 1980s, has been done in Scotland. Another good example is the Energy for All campaign, launched by Fuel Poverty Action, which now has widespread support.

An example I know at first hand is that of our campaigns around transport issues in London. A couple of years ago we had to face the fact that our long-running campaign to stop the Silvertown tunnel, which will produce more road traffic and therefore more carbon emissions, had failed. The tunnel will open in April.

In discussions about how to keep together the unity and goodwill we had built up, a number of us felt that we should become more politically ambitious, not less, and advocate policies that clearly address social inequality at the same time as addressing climate and air pollution. This brought us to the demand for free public transport and the formation of Fare Free London.

Although this is a very new campaign, we have had nothing but positive responses, from unions representing transport workers and many other organisations.

We hope that, by shouting more loudly about this, we will cut right across the demoralising political diversion, launched by the populist right at the Uxbridge by-election and shamefully latched on to by some Labour right wingers, around the Ultra Low Emission Zone.

The call for free public transport flies in the face of thirty years of neoliberalism, opens the city to all and strikes a blow for social justice, and can also help to get cars off the road and make demonstrable progress towards decarbonisation. Nothing would make us happier than to see this issue taken up in other parts of the country and to move towards a Fare Free UK campaign. SP, 12 February 2025.

[1] The CCC does not say what proportion of the global budget it thinks the UK could fairly use. Instead it makes a political judgement about what a rich country, with a long history of fossil-fuel-infused imperialism, can manage. In its own words, it starts with what it deems to be “feasible limits for ambitious but credible emissions reductions targets in the near term” (Sixth Carbon Budget report, pages 319-325)

[2] I set out this argument in more detail in a talk at the Rosa Luxemburg foundation in Berlin, and in my book Burning Up: a global history of fossil fuel consumption