At the Scot.E3 conference in Edinburgh on 18 October 2025 – Pete Roche led a workshop on nuclear power. These are his slides.

Pete produces a news digest Daily Nuclear, Energy and Climate news you can subscribe to it here.

Pete Roche’s slides from the workshop on nuclear power at the Scot.E3 conference

At the Scot.E3 conference in Edinburgh on 18 October 2025 – Pete Roche led a workshop on nuclear power. These are his slides.

Pete produces a news digest Daily Nuclear, Energy and Climate news you can subscribe to it here.

Ideological delusions and military secrecy that this generated has left Britain with one of the most uneconomic and unreliable power generation liabilities on the planet

The second part of an article by Scot.E3 activist Brian Parkin which was first published on the rs21 website on August 18, 2023. It (and the first part) provides useful background for the discussion on nuclear power that took place on October 18 2025 at the Scot.E3 conference.

In the first part of this short series, Brian Parkin showed how Britain’s nuclear power programme was a consequence of a nuclear weapons project intended to maintain Britain as a top flight imperialist nation. Here he explains how the ideological delusions and military secrecy that this generated has left Britain with one of the most uneconomic and unreliable power generation liabilities on the planet.

British governments after 1945 pursued a consensus of national recovery based on the re-energising of a depleted economy via new technologies and a welfare state social contract, to drive up productivity and profits to a level capable of sustaining Britain as a world power.

But the post-war ‘spheres of influences agreement’ of 1945 between the USA, Russia and Britain rapidly gave way to the Cold War and a new arms race. The Cold War divided the world into two armed camps, and with the formation of NATO in 1949, much of western Europe fell under the leadership of the USA against the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies. A year later, with the outbreak of the Korean War, it became clear that sections of the US military were lobbying for the use of nuclear weapons as first strike options.

What was clear within this new order was that Britain’s sphere of influence had dissipated into that marked out by the US nuclear super-power. But Britain nevertheless persisted with its own atomic bomb programme, as well as a V bomber programme as the means of delivering it. For Britain’s cold warriors, this was central to a military first-strike nuclear capacity which would keep them on a par with the USA. As the armed forces Chiefs of Staff Committee put it: ‘If we did not develop megaton weapons (hydrogen bombs), we would sacrifice immediately, and in perpetuity, our status as a first-class power’

This ambition was under-written by a total of six Magnox reactors – two at Calder Hall (now Sellafield) and four at Chapelcross in Dumfries – which were central to western plutonium production for H-bombs. By 1958 these reactors had a total capacity of 250 Mw of electrical output. But like the commercial Magnox stations to follow, these reactors proved at times to be unreliable, and the technology posed dangerous challenges. And while Britain was a useful source of cheap plutonium, the USA harboured doubts regarding Britain’s ability to sustain both the empire and a first strike nuclear capability.

Then in 1958, the first British H-bomb test took place on Christmas Island in the Pacific. This was followed by an amendment of the US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement, mainly as a means of controlling British nuclear activity by limiting its share of targets within USSR airspace. For a while the plutonium deal with the US remained a one-way street, until UK nuclear strategy became based almost entirely on H-bombs. This now meant the Britain becoming dependent on the US for its supply of tritium (an isotope of hydrogen) necessary for completing the reaction implosion, and thereby boosting the nuclear yield. This was the first stage in the unravelling of the myth of Britain’s ‘independent’ nuclear weapons.

Perhaps the most farcical aspect of the nuclear ‘special relationship’ was the complete American control over Operation Blue Danube – the joint USA-UK European nuclear attack plan. This gave the USA the power of veto over any first strike by the RAF. Overall American command of Nuclear Forces Europe meant that all nuclear weapons, even those at RAF V bomber bases, were in practice American property. All nuclear weapons manuals, fuses, fuse locks and fuse codes were kept in a secure vault on the RAF base, and the agreement provided that ‘…in the event of any RAF personnel attempting to obtain any secured items without superior and strategic authorisation, the [American] marine guards should exercise the duty to shoot (him/her/them) dead’.

Following the successful production of plutonium from the initial Magnox reactors, the Labour governments of the 1960s decided to proceed with a large-scale civil nuclear power programme. Any doubts regarding the costs of this venture were set aside by the strategic ‘need’ for plutonium, and the belief in nuclear power as protection against a possible miners’ strike. Given such strategic values, even the most basic cost-benefit analysis was regarded as wholly unnecessary.

But in 1988 all of the UK’s nuclear power secrets fell onto the desks of the National Union of Mineworkers Research Department, with the performance and costs of every reactor revealed. They showed that Magnox units constructed under ‘even under the most favourable and lowest Treasury discount (interest) rates, had at best performed at twice the cost of coal-fired stations’. They were hopelessly inefficient, in large part due to inherent design flaws such as fuel-rod alloys with a tendency to react explosively on contact with water, and graphite cores which could start to burn at high reactor temperatures. For these reasons, Magnox stations had never run at full capacity.

The figures were even more dismal for the second generation of Advanced Gas (cooled) Reactors (AGRs). Intended to run continually while being re-fuelled, these reactors experienced both fuel rod and control rod jamming. Steam temperatures were rarely optimal and heat exchangers often over-heated. These flaws combined to make them impossible to run at anything like full capacity, with utilisation sometimes as low as 18%. EDF, which would later take them over for almost nothing, described them as ‘basket cases’. One Treasury official in the run-up to electricity privatisation described them as ‘…the most expensive engineering folly ever under-written by the UK taxpayer’.

The super-power dreams embodied in the V bombers had quickly foundered on Russian advances in air defence. With the shooting down of a US spy-plane high over central Russia in 1960, it was clear that no RAF plane with atom-bombs was going to reach its target. In a way this suited some American strategic thinking, as shown by a White House directive of April 1961 which called for a ‘downgrading’ of the ‘special relationship’ and for ‘forcing a greater UK integration into Europe’.

This allied integration could best be hurried by ‘not prolonging the UK bomber force’– a task quickly achieved through the American failure to complete air-launched missiles upon which the RAF pinned its future strategic role: first Bluestreak (abandoned in 1960) and then the Skybolt (scrapped 1961). But the US was sensitive regarding ‘The UK’s loss of prestige and self-esteem’, hence the sop to share in its Polaris nuclear submarine deterrent, by basing the American vessels at Holy Loch, just 25 miles from Glasgow.

The eventual privatisation of the UK electricity industry went ahead in 1990, but only on the basis of the government footing the bill for untold nuclear liabilities, and the power stations themselves being split between two companies: Magnox Ltd, a wholly government operation set up prior to the oldest stations being handed over to a Nuclear Decommissioning Agency; and EDF, which acquired the AGRs for a notional peppercorn price, and was also allowed to operate its own power sales company.

The British nuclear power project arose from what was essentially an imperialist H-bomb imperative. As such, it escaped any public economic scrutiny. Instead, it became a key component of the post-1945 great British super-power illusion. Failures in the Magnox reactors were denied because their main job was to produce plutonium for the British nuclear ‘deterrent’. That same arrogant disregard of accountability and high secrecy still marks the nuclear power project to this day.

And now of the AGR fleet, only Heysham 2, Hartlepool and Torness remain in operation, up to 2028, at which point the highly subsidised Pressurised Water Reactor at Sizewell B (the only one ever built in Britain) will be the only pre-privatisation nuclear station left running. When they close, the costs of decommissioning will fall to the tax-payer, a bill that may well run into the next century. But we can be certain of one thing: the plutonium breeding reliabilities of Calder Hall, Chapelcross and the undisclosed number of ‘civil’ Magnox’s. Because somewhere at the leaking, creaking and decaying Sellafield complex, there are 139 metric tonnes of the deadliest material known to humankind with a half-life of 82 million years.

Why is nuclear power, a persistently failed energy technology, still so important to the British ruling class.

This article by Scot.E3 activist Brian Parkin was first published on the rs21 website on July 22, 2023. It (and its second part) provides useful background for the discussion on nuclear power that took place on October 18 2025 at the Scot.E3 conference.

After seventy years of scientific effort and countless investments, the holy grail of ‘electricity too cheap to meter’ remains as elusive as ever. Here Brian Parkin searches for reasons why a persistently failed energy technology is still so important to the British ruling class.

The Attlee Labour government of 1945-50 was committed to both a radical social policy programme at home and a colonial-imperialist continuity project abroad – the latter very much approved of by the British ruling class. Before the end of World War II, allied summit conferences at Moscow, Tehran and Yalta had produced a post-war agreement on ‘spheres of influence’ where the USA, USSR and Britain would control their respective allies, colonies, protectorates or dominions as spoils from their joint wartime efforts. But this was not an alliance of equals: the USSR was economically devastated, Britain was economically exhausted, while the USA was on the edge of what was to become the biggest and most protracted economic boom in the history of capitalism.

The USA had also, via the ‘Manhattan programme’, acquired the most devastating weapon ever – the nuclear bomb. Despite the involvement of UK scientists, the USA was initially not prepared to share its bomb making secrets with Britain. And furthermore, the USA was against the UK and France retaining their colonial empires.

A clandestine British nuclear programme had begun in 1940, and with the involvement of British scientists in the US nuclear project, the idea of ‘catching up with the Yanks’ almost counterbalanced the losing of empire, and led to hopes of a recovery of imperial status by other means. So it was not long before construction began on a nuclear facility at Windscale in Cumbria (renamed Sellafield in 1981), along with what was initially the highly secret facility at Aldermaston in Berkshire.

These developments arose from a secret decision taken by a small meeting – GEN 75, in January 1947 – when despite an austerity economy it was agreed that the UK should defy the USA’s intransigence and go ahead with its own nuclear weapons programme. As Ernest Bevan, Foreign Secretary and former right wing union boss said: We’ve got to have this thing over here. We’ve got to have the bloody Union Jack on top of it!’

By 1950 a reactor at Windscale had produced highly fissionable uranium235 (the ‘active ingredient’ of an atomic bomb), and by 1952 had produced enough for the first British bomb test on October 3 that year. Then, by stepping up its Magnox reactor programme, Britain was able to produce sufficient plutonium239 for a hydrogen bomb test on May 15 1957. But this came at a high cost. On October 10 1957 Unit One of a Magnox reactor core became over-critical, to the extent that its graphite core caught fire, and for three days released the highly dangerous isotope iodine131 to the outside atmosphere, which on a conservative estimate caused over 400 cancer deaths.

News of this incident was kept confidential, mainly to prevent information getting to a USA government unconvinced that Britain would be a reliable nuclear partner. This was a particularly important as by then a considerable proportion of the plutonium for the USA’s weapons programme was coming from the UK Magnox reactors.

In 1945, largely at the instigation of the USA, the United Nations held its inaugural session in California. As the war’s biggest victor, the USA wanted to legislate for a world fit for American capitalism. The United Nations gave this a semblance of legitimacy, though it was dominated by a Security Council mostly composed of American allies. And although Britain was on the Council, fear for its fading imperial lustre spurred the Labour government to press ahead to become a paid-up member of the ‘nuclear club’.

But nuclear club membership was nothing without a means of delivery. So in 1947 the government instructed the Royal Air Force to issue specifications and tenders for a new generation of jet-powered long-range, high altitude bombers capable of carrying and dropping nuclear bombs on what, by now, were going to be Russian targets.

By 1952 the UK’s first nuclear-capable bomber – the Vickers Valiant – flew. At that time, the intention was to keep at the forefront of a Western first-strike nuclear alliance, while never forgetting the longer-range requirements of rule over what was left of the empire, and the Commonwealth – hence the presence of V bombers in Rhodesia (the colonial name for Zimbabwe) and Malaysia as late as the mid-1960’s.

By 1964, the RAF had an incredible 159 total of Valiant, Vulcan and Victor bombers, each capable of being airborne in three minutes and in Russian airspace within 72 minutes. However, Russian air-defences had improved to the extent that the V bombers’ maximum altitudes rendered them sitting ducks by around 1965. So then a medium-range series of joint US/UK air launched missiles was considered, only for the US to pull out of the project. The Vulcans last flew in the Falklands war in 1982, carrying out a long-range and not very successful bombing of Port Stanley Airport, before being taken out of service.

On August 27 1957, a small Magnox reactor on the Calder Hall site at Windscale had some of its secondary coolant steam diverted through a turbine to mark the beginning of the world’s civil nuclear power age. The initial contribution to the National Grid was an intermittent four megawatts (then enough to power some 4,000 homes). The idea of nuclear power from a weapons grade plutonium reactor had arisen due to the sheer waste heat given off, and the huge effort required in cooling the process to a safe level.

This ‘seminal’ event was the first step to what was untruthfully called a peaceful civil nuclear power age. What it rather was, was the continuation of a plutonium programme with a significant power byproduct. The military-civil linkage was still intact – as was the superpower nuclear delusion which had spawned it.

The modest Calder Hall event gave rise to a speculative frenzy of nuclear optimism. The very idea of power from nuclear fission created an aura of technological supremacy, and the illusion that Britain could become a leadership nation unafraid of the challenges of power and the military means of exercising it. Because something like that kind of ideological hubris must have fuelled what came next.

In 1959 it was agreed to proceed with a nuclear power programme with a technology ‘proved’ by the Magnox experience at Windscale. This meant a generation of new reactors fuelled by ‘natural’ uranium with graphite moderated cores and with a primary carbon dioxide cooling system. But although the main aim of the new Magnox stations was the production of electricity, some plutonium would be a secondary byproduct.

At this point it is worth recalling the political/economic situation the fading British empire had to face. In 1956, a failed military intervention by Britain and France had failed to resolve the ‘Suez crisis’, sparked by the fear of losing of the Suez canal as a gateway to Asia and Gulf oil supplies. At this point a government committee decided that for energy security reasons, it was decided that Britain would require 6,000 megawatts of nuclear capacity by 1965.

This bizarre reasoning – Britain did not use oil for power generation – was primarily rooted in a ruling class paranoia, which saw nuclear power capacity as protection against a possible miners’ strike. Here nuclear power provided balm to a fading imperial delusion and a deep and abiding fear of organised labour. In Part 2 we shall see how ignorance, hubris and fear continue to fuel the British nuclear tragi-comedy.

Pete Cannell looks at the way in which the climate crisis and militarism are intertwined

Annual global expenditure on arms and warfare is of the same order of magnitude as the best estimates of the annual funding required to make a worldwide transition to a zero-carbon economy.

The US military-industrial complex is by far the biggest component producer of carbon emissions. It’s hard to get completely accurate figures since around the world nations simply fail to report carbon emissions from their armed forces or conceal the emissions under other headings. And generally, they are given a free ride – scientific reports – for example the IPCC reports on the state of the climate – scarcely mention the impact of military emissions. But it’s estimated that the military contribute something like five and a half per cent of global emissions – more than all the carbon emissions from Russia. Military kit is heavy, expensive and fuel greedy. To travel 1km a Humvee armoured car produces ten times the carbon emissions of an average car, an F35 jet aircraft as much as one hundred cars and one of the new British aircraft carriers is equivalent to five thousand five hundred cars. Around the world there are big increases in military expenditure taking place – the increases proposed for NATO amount to the equivalent emissions of 200 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2e).

When weapon systems are deployed and used the environmental cost is magnified. Looking at the use of arms in Gaza since 7 October 2023, One Earth found that 99% of emissions were due to Israel amounting to more than 1.8 million tonnes CO2e. Total emissions from the onslaught on this tiny area exceeded the combined annual total of Costa Rica and Estonia. But these totals are tiny compared with the carbon cost of rebuilding Gaza which is reckoned to be around 29.4 million tonnes CO2e. And of course, the environmental impact is not just about carbon emissions. It includes pollution, poisoning through residues from shells and explosives and contamination of ground water. Low level nuclear radiation from the dust produced using depleted Uranium shells is still causing deaths and birth defects in Iraq more than two decades after the second Iraq war. Then there’s the degradation of the natural environment and agricultural land which in its turn adds to climate emissions.All of this highlights the importance of the military as a significant contributor to carbon emission and environmental destruction.

However, I’d argue that most important is the structural role that arms production has in the global capitalist economy. Scotland is a good case study. The arms industry, including the nuclear base on the Clyde, is quite small in terms of numbers employed and even in terms of its percentage of GDP. But it has a status that no other industry has – access to and support from government. Investment is prioritised above the threat of climate change. above that for climate. Indeed, the latter is left to the private sector or marginalised. The skills needed to work in the industry are often transferable to renewables and the building of a sustainable economy. The arms industry is centralised, securitised, secretive and immune to oversight and criticism – all this justified by appeals to the ideology of national interest. More generally the arms industry is at the intersection of global capitalism, imperialism, and environmental destruction. The deep connections between middle east oil and gas (and its impact on the environment) and the arms trade are clearly drawn out in Adam Hanieh’s Crude Capitalism

This article by Simon Pirani was first published in Capitalism Nature Socialism journal, August 2024 and reproduced on the People and Nature blog.

Matthew Huber and Fred Stafford’s insistence that “electricity is poised to be a central site of political struggle in the twenty-first century” (2023, 65) is welcome and timely. But the approach they set out in “Socialist Politics and the Electricity Grid,” in Catalyst journal, is flawed. They argue that the basis for a socialist energy supply system is centralised electricity generation, primarily from nuclear power; that renewable electricity generation should play only a minor role; and that decentralised renewables are unworthy of support, for both technological and political reasons. Indeed, Huber adds, in an article on the Unherd website (2023), neoliberalism fostered decentralised renewables while undermining centralised generation, and socialists seduced by “green” renewables have unwittingly become neoliberalism’s allies.

In this response, I suggest, first, that nuclear power has overcome none of the problems that led several generations of socialists to oppose it (links with the military, absence of waste disposal, and so on), and that it features only in the most impoverished views of the transition away from fossil fuels and the most conservative, state-centred versions of socialism. Second, I discuss the decades-long trend towards decentralisation of electricity networks – a reality for which Huber and Stafford fail to account. I argue that our focus should shift away from outworn pro-nuclear arguments towards a discussion of whether, and how, socialism can challenge capital’s control of electricity technologies, including decentralised renewables, and turn them to our advantage. Third, I challenge Huber and Stafford’s claims that renewables are, by comparison to nuclear, inherently inimical to labour organisation and to public forms of ownership. Finally, I question the misrepresentations on which Huber relies in an account of the relationship through history of energy technologies and neoliberalism. I build on arguments presented previously (Pirani 2023a, 2023b, 2023c.)

Nuclear and renewables

In their Catalyst article, Huber and Stafford (2023, 75) write: “From a socialist perspective aiming for reliable nonstop, zero-carbon power, nuclear energy would be the foundation of the grid.” The risks associated with nuclear are exaggerated in popular attitudes; problems with radioactive waste have been “overstated.” They do not engage with researchers of nuclear who assert that there is: (1) no long-term solution to the waste problem; (2) that there is “no working deep repository for high level waste anywhere”, despite limited progress in Finland and Sweden (Cullen 2021); (3) that a solution is “decades away”; and (4) that plans for new nuclear in the UK should be frozen “until we have a geological disposal facility”, which is timetabled for the 2040s but likely to take longer (Laville 2022).

Huber and Stafford pass over in silence the way that nuclear power implies and requires a strong state, and its close connection with the military – an omission all the more remarkable, given the occupation since 2022 of Europe’s largest nuclear plant, at Zaporizhzhia, by the Russian army, which bears responsibility for the collapse of the nearby Kakhovka hydro plant (Glantz et al. 2023). For the rich tradition of socialist writing on technology, the nuclear-military connection is not only about such “accidents,” but about deeper-going economic and technological relationships. Only nuclear reactors produce the fissile material needed for nuclear bombs; military imperatives shape national industrial supply chains more broadly; the overlaps in education, design, research and security are all extensively researched. Civilian nuclear power has been in long-term decline due to its high cost, but has proved “surprisingly resilient” to market conditions in a limited group of countries, due to this interdependence (Stirling and Johnstone 2018).

Ultimately, the way socialists see nuclear power is bound up with our views of potential post-capitalist futures. Huber and Stafford’s vision (2023, 79) is “of ‘big public power’, in which the public sector would subsidise the mass buildout of large-scale zero-carbon energy generation infrastructure including nuclear power and, where geography suits, renewables.” Against this, I commend the view held by Cullen (2021) that nuclear power is “antithetical to the world we want to see. From its origin as a figleaf to distract us from the grim truth of mutually assured destruction, to its recent resurrection as a bogus solution to climate change, it is inherently bound up with violent state forms and paranoid and secretive hierarchies.”

Views of nuclear also vary according to our approaches to the transition away from fossil fuels. The two most vital changes needed are: (1) to transform the way final energy is used (e.g. by insulating homes to reduce the need for heating, improving public transport to reduce the need for cars, ending wasteful forms of consumption), and (2) to reduce throughput of energy in technological systems (e.g. by replacing gas boilers with heat pumps). The remaining energy required must be produced with non-fossil-fuel technologies, of which renewables and nuclear are the most developed. The copious scenario analysis literature shows that climate change can only be dealt with in the course of deep-going social transformations (Grubler et al. 2018, van Vuuren et al. 2018, Allwood et al. 2019). For socialists these transformations are bound up with overcoming and superceding capitalism (Pirani 2018, Pirani, 2023a).

For the present discussion, there are three relevant points that I would like to emphasise. First, climate change deprives us of time. Nuclear power stations take many years to build, while decentralised renewable energy systems do not. Second, the future of electricity networks must be considered in the context of broader economic changes overshadowed by climate change, and the need for transforming final energy use and reducing throughput, mentioned above. (In his writing on “degrowth,” discussed elsewhere, Huber (2022, 31-32 and 162-175) has remained agnostic on energy consumption and throughput scenarios.) Third, highly flexible electricity networks are both necessary for reducing throughput and transforming final energy use – and, happily, also facilitate decentralised renewables. Integrating nuclear power stations that generate large, unchanging quantities of electricity into such networks may be less easy.

Under the present political conditions, in which labour movements and social movements are struggling for change under capitalism, choices made by the state about which energy resources to invest in do matter. Huber and Stafford (2023, 78) advocate opting for nuclear, despite the extraordinary expense: it “needs socialism to grow – or at least a form of public investment that socialises the costs of construction and does not privatise the gains.” The corollary should be spelled out: resources invested in nuclear would not be invested in renewables.

Discussions among socialists would benefit from greater attention to the transition scenarios mentioned above, which afford a way into some of the social and technological issues. It would also be worthwhile to develop a socialist critique of “100 percent renewables” scenarios (i.e. models depicting hypothetical paths towards electricity networks run solely from renewable electricity, without any fossil fuels or nuclear) developed by researchers from engineering and scientific backgrounds (Pirani 2023d). Huber and Stafford, characteristically, dismiss these scenarios as “largely based on the models of one researcher, Mark Z. Jacobson.” They are mistaken. A recent survey covered the work of some thirteen research teams (Heard et al. 2017, Brown et al. 2018).

Renewables and network integration

Huber and Stafford (2023, 65-66) propose “core principles” on which to base a socialist approach to electricity. They argue that electricity should be produced as a public good, rather than a commodity, that control by capital will always subvert this goal, and that for this reason “public or alternative ownership structures” are crucial. All this is welcome. Further, they propose that electricity is a “complex material system of production,” conducive to socialist planning, which “consequently requires a deep materialist understanding of how it works and how it might be transformed.” In my view, the conclusions they draw from this – that this understanding points toward “the importance of centralised, large-scale reliable power generation like hydroelectric dams and nuclear power, as opposed to decentralised, small-scale and intermittent forms of power like rooftop solar panels” – need to be challenged.

Huber and Stafford refer repeatedly to the supposed threat to electricity systems from decentralised renewables: intermittency “creates unavoidable problems for grid planning”; when there is too much wind and solar, that leads to curtailment, and when there is too little, electricity prices go up. They highlight the dangers of blackouts to “the very survival of the system,” but, unfortunately, remain silent on the fact that the world’s most devastating electricity blackouts (Puerto Rico 2017, Bangladesh 2022, Pakistan 2023) occurred in fossil-fuel-dominated networks for reasons that had nothing to do with renewables. They claim, mistakenly, that it is “still not clear how [renewables] can provide reliable power for the entire grid the way centralised power plants do today.”

These assertions are disproved by reality. While renewables’ share of global primary energy supply remains pitifully small, renewables generate a substantial share of electricity in a significant number of rich countries. Wind and solar account for 41 percent, 40 percent and 35 percent respectively of electricity generated in Germany, the UK and Spain, three of the largest European economies, and 43 percent in California, which consumes more electricity than most nations. Denmark generates 61 percent of its electricity from wind and solar and 23 percent from modern biofuel use. Variable renewables’ share of electricity generation in Scotland averaged 60 percent in 2019-21. This expansion of renewables, that like fossil fuels and nuclear are predominantly controlled by corporations and the state, is fraught with dangers, not least to the people of countries being plundered for minerals used in equipment manufacture. Grid integration, though, is less a danger, and more an engineering challenge (Pirani 2023b).

Wherever variable renewables expand, network upgrades are required. In particular, grids supplied by a large proportion of renewable generation need more, and newer, ways to store energy and to ensure grid stability. Because electricity grids are controlled by capital, just as the power stations are, the infrastructure investment needed to modernise them lags far behind the shift towards renewables in power generation. The most common problems caused by this failure to modernise are shortages of transmission and storage capacity (see e.g. IRENA 2023b, 11-14). The chronic level of curtailment of wind power in China in the late 2010s is noteworthy; so is the success of electricity transmission and distribution companies in fixing it (Chen et al. 2022) In the USA and Europe, the years-long queues for electricity generators to get a grid connection have become public scandals (Rand et al. 2022) But the underlying cause of poor infrastructure is not renewable technologies, but underinvestment. And the cause of that is, often, neoliberalism.

As for Huber and Stafford’s point that wholesale electricity prices may rise when less power than expected comes from wind – well, that’s how (pending improved weather forecasting) markets regulate supply and demand. (The example they cite, of too little wind in Europe in December 2022, is factually incorrect. See Pirani 2023b, section 2.4.) The problem is not the wind, it is the way markets function.

Not only does Huber and Stafford’s “deep materialist understanding” fail to explain what is going on in Scotland, California, and elsewhere; it also omits any account of the trends over several decades towards decentralisation of electricity networks, and, more recently, from uni-directional to multi-directional operation. The networks installed in rich countries in the first half of the 20th century, and across much of the global south in the second half, were designed to carry electricity in one direction: mostly from big coal, gas and nuclear power stations, to users. Peak centralisation was in the 1970s. Combined heat and power plants, and power stations using combined-cycle gas turbines (CCGT) built in the 1980s and 90s were smaller; wind and solar plants, even utility-scale ones, smaller still. (Patterson 1999, 68-70, 72-75, 114-116; IRENA 2023a, 17-18, 64-66).

As the number and type of electricity sources increases, networks adapt to manage their inputs, in the context of the “third industrial revolution,” that started with semiconductors and gave rise to a new generation of technology, including personal computers, mobile phones and the internet. The next big change, now getting underway, is towards flows of electricity in multiple directions, with the potential for microgrids, including those using direct current only, and for supply by decentralised generators to local users. These changes raise vital political issues, including: (1) whether these decentralised technologies, which are largely but not completely developing under corporate and state control, have the potential to enhance, and be strengthened by, forms of social ownership and control, to work towards the decommodification of electricity; and (2) whether co-ops, community energy projects and municipal ownership forms may be stepping stones in these directions (Pirani 2023b.)

Huber and Stafford’s concern that the addition of renewables disrupts an existing system might have made sense ten or more years ago. But the technology – if not the economics – of electricity networks has moved on. Rather than engage with this reality, it is unfortunate that they fall back on the following polemical misrepresentations:

□ They quote Mark Nelson, a consultant and nuclear advocate, to the effect that “claiming cheap renewables are a viable solution for our grid system is like claiming flimsy tents are a viable solution for the housing crisis.” They incorrectly describe Nelson as an “energy analyst,” imputing to his words an authority they do not have.

□ Huber and Stafford claim that “cheap prices of renewable energy don’t include the transmission lines to their remote locales or the costly back-up required when the weather isn’t favourable,” and that “the limited use value of solar and wind” leads to “broader system costs” not covered by renewable generators. They ignore the complexities of the integration into grids of variable renewables, and the substantial body of research of the costs (e.g. Heptonstall and Gross 2021, IEA/NEA 2020, Elliott 2020, 7-9). They misrepresent modelling by Robert Idel to create an exaggerated impression of renewables costs. (For details, see Pirani, 2023a, “Note: infrastructure costs.”) The simplified framing of renewables as an economic burden to an existing system has long been a staple of fossil-fuel-based generators’ propaganda, answered by mainstream energy economists with proposals for market reform and by socialists with calls for public ownership and decommodification. It has no place in a serious discussion.

□ Huber and Stafford pay unwarranted attention to the microscopic portion of off-grid solar in the global North, writing: “While the Elon Musks of the world hawk the benefits of ‘delinking’ from the grid through the individual purchases of rooftop solar equipment and battery storage, we must fight for the expansion of electricity as universal public infrastructure.” Yes, Elon Musk is a dangerous clown, and, yes, a small number of rich households may see rooftop solar as the road to a reactionary, isolationist, off-grid existence. But in the big picture, they are irrelevant. The overwhelming majority of rooftop solar, whether household, municipal or corporate, is connected to the grid. All these solar panels are part of a universal infrastructure. The barriers to that infrastructure being geared to use, and not profit, is not that the panels are decentralised, but that neither panels nor networks are publicly or commonly owned and controlled.

It would be regrettable if discussion among socialists were to be dominated by outdated pro-nuclear arguments, rather than by the real-world problems in electricity networks and other energy systems posed by climate change and the crises of capital. Collectively we should develop a critique of the work by engineers in politically mainstream contexts who assume markets as a key regulating mechanism (e.g. Cochran et al. 2014, Kroposki et al. 2017, Hanna et al. 2018), and build on arguments for greater public control (Elliott 2017, Elliott 2020, Kristov 2019). Research by a group of European scholars on the potential for flexible grids and decentralised renewables to open the way to forms of common ownership and to decommodification of electricity deserves our attention (Giotitsas et al. 2020; Giotitsas et al. 2022; Kostakis et al. 2020). They envisage “commons-based peer production,” under which “smart” technology is used not to trade electricity as a commodity but to share it as a common good; they show how software technologies that currently “align with the existing liberalised market with ancillary and balancing services” also “open up the possibility for democratising electricity if governed as a commons.”

Renewables, labour and socialism

Matthew Huber proposes that (i) renewable electricity generation is, by its nature, hostile to working-class organisation in a way that nuclear and hydro are not; (ii) decentralised technologies are poorly suited to public ownership, and that using them to enhance forms of social ownership at sub-national level is a blind alley; (iii) in any case such “localism” is at odds with Marxism; and (iv) there is a split in “the Left” between traditional labour unions that go with centralised generation, and “environmentalists and ecosocialists” who like decentralised renewables. I suggest that each link in this logical chain is broken.

Let us take up some of these arguments, which are important to the direction of the climate justice and labour movements.

Is electricity from renewables hostile to working-class organisation?

Huber (2023) writes, on the Unherd web site, that, in the USA in the 1980s, “the shift away from utilities and towards decentralised merchant generation explicitly undermined the labour unions who had built up their power under the older, established utility system. […] It is much easier to organise workers in centralised power plants than scattered solar and wind farms whose [sic], after all, only provide temporary construction jobs.”

The message – that solar and wind are bad for unions, large nuclear and hydro are good for unions – is oversimplified. The break-up of the US utility system did indeed damage the unions, with the loss of 150,000 unionised jobs (Beder 2003, 125). But renewables played a negligible part: those merchant generators used gas and some nuclear instead. And there was a context, which Huber does not mention: the gigantic, global shifts in labour markets that has made precariousness the “normal condition of labour under capitalism,” especially outside the rich world and among women in rich countries (Huws 2019, 51-66).

It is not in dispute that many renewable energy and other “green tech” companies are ferociously anti-union, just as many nuclear companies are anti-union. Huber and Stafford (2023) point to energy sector unions that favour nuclear, and argue that we should “listen to what these workers and unions say.” Yes, we should. But we should also probe the extent to which unions really speak for workers. And we should confront the reality that in this case, as in others, there may be tensions between some workers’ sectional interests and the aims of the workers’ movement more widely.

Are decentralised technologies poorly suited to public ownership?

In his article for Unherd, and his book on climate change, Huber shows little sympathy for the widespread movement towards co-operative and municipal ownership of electricity generation, facilitated by renewables technologies. He opposes the “localist path” as a matter of principle. It is “deeply at odds with the traditional Marxist vision of transforming social production,” he writes (2022, 250). And to drive the point home: “Duke Energy does not care if you set up a locally owned micro-grid.” It should be noted, first, that the “traditional Marxist vision” had a far more generous attitude to coops: in his classic critique of utopian socialism, Friedrich Engels (1882) went out of his way to welcome Robert Owen’s co-ops, envisaged as “transition measures to the complete communistic organisation of society,” for having “given practical proof that the merchant and the manufacturer are socially quite unnecessary.”

Second, and relevant to 21st century practice, the limits to the potential of co-ops and municipal forms of ownership of electricity generation have not yet been sufficiently tested. The valuable contributions to discussion of this include: (1) the assessment by Trade Unions for Energy Democracy of the damage done to co-ops and community energy projects in Europe by pro-business market regulation (Sweeney et al. 2020); (2) commentary on the legislation passed in New York directing the municipal power company to plan, build and operate renewables projects (Dawson 2023); and (3) research on the damaging impact of state and corporate power on efforts to use co-operative and community energy forms to advance electrification in developing countries (Baker 2023, Ulsrud 2020). Huber’s blanket rejection of “localism” obstructs these important discussions, and offers a conservative view of socialism as something brought about primarily or only by state action at national level.

Is localism at odds with Marxism?

In his polemic against “localism,” Huber (2022, 250) writes that “capitalism produces the material basis for emancipation through the development of large-scale and ever-more centralised industry.” Marx, he writes, explained that capitalism “tends to centralise capital through the ‘expropriation of many capitalists by a few’. But through this centralisation process, production itself becomes more and more socialised.” This is a misunderstanding of Marx’s point, in my view. When writing about the expropriation of many capitalists by a few, he was referring to the centralising effect of money capital and the development of corporations. But it was the socialised nature of production under capitalism, not centralisation as such, that in Marx’s view laid the basis for social ownership and control. To conclude from this a principled approval of “centralisation” makes little sense. To transpose it to a 21st century context, to claim that Marxism embraces the physical centralisation of electricity generation, makes even less sense.

Is there a split between labour and ecosocialists over decentralised renewables?

For Huber and Stafford (2023, 67), those who see potential for building elements of opposition to capitalism in co-ops, community energy projects or municipal ownership of decentralised renewables, are on the wrong side of a political divide. They see a “split within the capitalist class” between “historically embedded investor-owned utilities” who claim a commitment to reliability, and “industrial consumers of electricity” who seek flexible supply contracts and “emphasise their green credentials.” This split, they write, is replicated in “the Left”: “traditional labour unions” are siding with utilities, and therefore with centralised generation, while “environmentalists and ecosocialists” are with “renewable energy producers, Google and increased marketisation of electricity.”

This is a contrived argument. The division between US utilities and industrial electricity consumers is not one of principle, it is simply sellers vs buyers. And the identification of more renewables with “increased marketisation” is a myth: the fastest expansion of renewable generation is in China, one of the most heavily regulated electricity markets on earth. As for the supposed alliance between “environmentalists and ecosocialists” with “increased marketisation”, “Google,” and so on, this is a declaration of guilt by association.

Renewables and neoliberalism

So powerful is his crusading fervour against decentralised renewables, that Huber (2023) does the following: (i) paints decentralisation as a product of neoliberalism; (ii) claims inherent links between renewables and private capital, and between nuclear and public ownership; and (iii) sees environmentalists and leftists who embrace renewable electricity dragged along behind an “anti-social [neoliberal] reaction against society itself.” None of this withstands scrutiny.

Is decentralisation a product of neoliberalism?

Huber writes that, in the 1970s and 80s, neoliberalism set out to demolish “large, rigid institutions” of the post-war boom – unions, universities, even monopolistic corporations – “in favour of smaller, more flexible production guided by a decentralised price mechanism.” He argues that this supposed “decentralisation” underpinned the rise of renewable electricity generation. But even in its use of price mechanisms, neoliberalism was the very opposite of “decentralised.” The weapons it wielded on behalf of big, centralised corporations included deregulation of finance capital, by such measures as abolition of capital controls and expansion of offshore financial zones. Financial markets were “globalised,” in many cases subordinating national markets to internationally-determined prices.

Huber cites the neoliberal ideologue Friedrich Hayek writing about “decentralised planning.” But those words tell us little about the neoliberalism that actually existed, which Marxists long ago understood as a “political project to re-establish the conditions for capital accumulation and to restore the power of economic elites” rather than a “utopian project to realise a theoretical design [of markets],” (Harvey 2005, 12-19; Cahill and Konings 2017, 94-98).

Are renewables inherently suited to private capital?

Huber also writes that neoliberal ideology “seized the [US] electricity sector” in the late 1970s; for neoliberals, electric utilities “epitomised the kind of inflexible and corrupt institutions targeted for demolition”; environmentalist ideology of the time, epitomised by Amory Lovins’s “soft energy path,” “conformed to this neoliberal critique of ‘big’ and ‘centralised’ utilities.” Thus, “against a complex and centrally-planned system, ‘grassroots’ local communities aspired to get off the grid entirely,” while at the policy level a “vision of a decentralised renewable-powered utopia actually accompanied a broader project of electricity deregulation” under president Jimmy Carter.

First, let us put aside local communities who aspired to get off grid. They are interesting for the history of counter-culture, but irrelevant to energy policy.

Second, recall the context for the neoliberal reforms in the US electricity sector: the “energy crisis” caused by the assertion of pricing power by Middle Eastern oil producers in 1973, and the dominant capitalist powers’ alarm at the shifting terms of trade. This produced a politically-driven investment boom in nuclear and other non-fossil energy that overlapped with market liberalisation.

Third, the technological development of wind turbines was taken on by the state, via NASA; the speculative wind “boom” that followed during the 1980s was a footnote in the story of electricity, that produced less per year than one typical power station’s output; and while as Huber notes neoliberal market reform helped the corporations who dabbled in wind, it was a tax dodge (the Energy Tax Act) that was decisive. When this subsidy was junked, the “boom” collapsed (Owens 2019, Newton 2015). Only in the 2000s did wind power expand significantly in the USA.

Huber’s “new class of capitalists building renewable energy projects,” who “need not care about the grid as a social system” is, at least in the 1980s and 90s, a phantom. His connection between Lovins’s (1979) “soft energy paths” argument (which in the 1970s was anyway focused on energy conservation and cogeneration, and not on renewable power), Carter’s market reforms, and the expansion of decentralised renewables a quarter of a century later, is a specious construct.

Yes, the market reforms weakened the utilities and reinforced wholesale electricity markets. Gas rose, coal retreated. But the overarching theme is not decentralisation, but neoliberal support for gigantic corporations, including the construction companies and nuclear generators whose lobbying led to a massive excess of generating capacity (Pope 2008.)

To tell this story as one in which renewables are identified with neoliberalism, and nuclear with public power, is to rewrite history in the service of ecomodernist ideology.

A brief glance outside the USA confirms that, as a rule in the 20th century, wind and solar technologies were developed by the state and by social movements; private capital only moved in later. In Denmark, the world’s leading developer of wind power, the initial impetus came from a community movement based on co-ops; later, the state, having accepted the dominance of wind power, brought in the corporations. In Germany, a parliamentary alliance of greens and social democrats gave the initial impetus, through state subsidies. Since the 2010s, China, where state direction of industrial policy is anything but neoliberal, has been overwhelmingly dominant in the production, export and deployment of renewable technologies (Maegaard 2013; Morris and Jungjohann 2016; Pirani 2023b.)

Leftists, environmentalists and a reaction against society

Huber also writes, with reference to the 1980s: “[I]f most of the 20th century was about large-scale social integration of complex industrial societies, the neoliberal turn represents an anti-social reaction against society itself. For parts of the right, there was ‘no such thing’ as society, only individuals. But the environmental Left made a comparable turn: large-scale complex industrial society was rejected in favour of a small-scale communitarian localism. In this framework, ‘communities’ could opt out of society and usher in democratic control over energy, food and life.”

Huber evidences this colourful denunciation by quoting the German philosopher Rudolf Bahro (“we must build up areas liberated from the industrial system”) – an absurd own goal, since, however widely you define the “left,” Bahro, by his own account and those of his colleagues, had in the 1980s long ceased to be part of it (Hart and Mehle 1998).

In contrast to Bahro’s drift to anti-industrial environmentalism, there is a wealth of socialist writing that saw capitalist social relations as the underlying cause of the 1970s “energy crisis” and environmental crises. Examples include the Italian autonomists who urged a “post-nuclear transition” that presupposed transforming “not only energy use but also the capitalist mode of production and social organisation” (Sapere 1985, 71), and the American writer Barry Commoner (1990, 193) who thought of environmentalism in terms of “transformation of the present structure of the technosphere,” in the context of social change.

Even André Gorz (1987, 19), perhaps the 1980s’ most forceful socialist proponent of decentralised energy, saw its development as inextricably bound up with social transformation. He wrote that objections could be raised to a focus on such technologies, on the grounds that “it is impossible to change the tools without transforming society as a whole.” “This objection is valid, providing it is not taken to mean that societal change and the acquisition of state power must precede technological change. For without changing the technology, the transformation of society will remain formal and illusory.”

It is to be hoped that collectively, we will develop a socialist approach to electricity systems, including the problems that decentralised renewables pose, in the context of the struggles for social justice and to tackle climate change. A robust critique of our above-mentioned predecessors would strengthen the foundations of such an approach. Huber’s misrepresentations of these writers as allies of neoliberalism is an unwelcome obstruction to such a critique that should be moved out of the way.

Conclusions

Renewable electricity generation is not perfect — the social and environmental impacts of its materials supply chains are only the most obvious of its drawbacks. But it operates without fossil fuels or carbon emissions. Unlike nuclear power, it is (i) free of inherent links with fearsome state structures and the military, and (ii) highly compatible with more flexible networks, reductions in throughput and rapid changes in energy end-use that are the most important ways of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The increasing decentralisation of electricity generation is not perfect either. It is a technological change that has been in progress for decades, in the context of the “third industrial revolution.” Huber and Stafford ignore this process, and suggest, mistakenly, that technological decentralisation equals political decentralisation, and that both are somehow inimical to working-class organisation and socialism. They ignore, too, the rich history of socialist writing on technology and its relationship to society, to construe a false alliance between nuclear power and working-class interests. To support this, Huber offers a sketched history of renewable electricity generation, rewritten to depict it as a child of neoliberalism, that is replete with distortions.

A starting-point for discussion on the role of electricity systems in the transition away from fossil fuels, and in struggles against capitalism, in my view, is an assessment of the technological changes underway, and the corrosive effect of the corporate and state interests under whose control it is taking place. Perspectives and policies must be considered together with the need for transformation of energy end use, for reduction of throughput and for the supply of electricity to the hundreds of millions of people who do not have it. In rich countries the potential of co-operative, municipal and other forms of public ownership must continue to be tested, alongside traditional demands for public ownership. Finally, the interests of workers directly employed by electricity companies must be considered not sectionally but as part of the broader working-class and societal interest.

□ With thanks to Daniel Faber and Marty deKadt for their comments on the draft of this article. All opinions expressed and mistakes made are mine. Simon Pirani.

□ Original of this article on the Capitalism Nature Socialism web site, on open access.

References

Allwood, J.M. et al. 2019. Absolute Zero: Delivering the UK’s climate change commitment with incremental changes to today’s technologies (University of Cambridge)

Baker, Lucy. 2023. “New frontiers of electricity capital: energy access in sub-Saharan Africa,” New Political Economy 28.2: 206-222.

Beder, Sharon. 2003. Power Play: the fight to control the world’s electricity New York: The New Press.

Brown, T.W. et al. 2018. “Response to ‘Burden of proof’,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 92, 834-847.

Cahill, Damien and Martijn Konings. 2017. Neoliberalism London: Polity.

Chen, Hao et al. 2022. “Winding down the wind power curtailment in China,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 167: 112725.

Cochran, J. et al. 2014. Flexibility in 21st Century Power Systems: 21st Century Power Partnership. Golden, Colorado: National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

Commoner Barry. 1990. Making Peace With the Planet. New York: The New Press.

Cullen, Dave. 2021. “Stop Trying to Make Nuclear Power Happen,” New Socialist, 16 October. https://newsocialist.org.uk/stop-trying-make-nuclear-power-happen/

Dawson, Ashley. 2023. “How to win a Green New Deal in your state,” The Nation, 11 May.

Elliott, David. 2017. Energy Storage Systems. Bristol: IOP Publishing.

Elliott, David. 2020. Renewable energy: can it deliver? London: Polity Press.

Engels Friedrich, 1882. Socialism utopian and scientific.

Giotitsas, Chris, et al. 2020. “From private to public governance: the case for reconfiguring energy systems as a commons,” Energy Research & Social Science 70: 101737.

Giotitsas, Chris, et al. 2022. “Energy governance as a commons: engineering alternative socio-technical configurations,” Energy Research & Social Science 84: 102354.

Glantz, James et al. 2023. “Why the evidence suggests Russia blew up the Kakhovka dam,” New York Times, 16 June.

Gorz, André. 1987. Ecology as Politics. London: Pluto Press.

Grubler, Arnalf et al. 2018. “A low energy demand scenario for meeting the 1.5°C target and sustainable development goals without negative emission technologies,” Nature Energy 3: 515-527.

Hanna, R. et al. 2018. Unlocking the potential of Energy Systems Integration: an Energy Futures Lab briefing paper. London: Imperial College.

Hart, James and Ullrich Melle. 1998. “On Rudolf Bahro,” Democracy and Nature 11/12.

Harvey, David. 2005. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heard, B.P. et al. 2017. “Burden of proof: a comprehensive review of the feasibility of 100% renewable-electricity systems,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 1122-1133.

Heptonstall, Philip and Robert Gross. 2021. “A systematic review of the costs and impacts of integrating variable renewables into power grids,” Nature Energy 6: 72-83

Huber, Matthew. 2022. Climate Change as Class War: building socialism on a warming planet. London: Verso.

Huber, Matthew. 2023. “Renewable energy’s progressive halo,” Unherd, 19 May 2023.

Huber, Matthew and Fred Stafford. 2023. “Socialist Politics and the Electricity Grid,” Catalyst 6:4, 62-93.

Huws, Ursula. 2019. Labour in Contemporary Capitalism: What Next?London: Palgrave Macmillan.

IEA/NEA. 2020. Projected Costs of Generating Electricity. https://www.iea.org/reports/projected-costs-of-generating-electricity-2020

IRENA. 2023a. Renewables 2023 Global Status report: Energy Supply module.

IRENA. 2023b. Renewables Global Status Report 2023: Energy Systems and Infrastructure module.

Kostakis, Vasily, et al. 2020. “From private to public governance: the case for reconfiguring energy systems as a commons,” Energy Research & Social Science 70: 101737.

Kristov, Lorenzo. 2019. “The Bottom-Up (R)Evolution of the Electric Power System: the Pathway to the Integrated-Decentralized System,” IEEE Power & Energy, March-April, 42-49.

Kroposki, B. et al. 2017. “Achieving a 100% renewable grid,” IEEE Power & Energy magazine, March-April, 61-73.

Laville, Sandra. 2022. “Push for new UK nuclear plants lacks facility for toxic waste,” The Guardian, 28 March.

Lovins, Amory. 1979. Soft Energy Paths. New York: Harper & Row.

Maegaard, Preben. 2013. “Towards public ownership and popular acceptance of renewable energy for the common good,” in Preben Maegaard, Anna Krenz and Wolfgang Palz, Wind Power for the World: international reviews and developments. London: Taylor & Francis.

Morris, Craig and Arne Jungjohann. 2016. Energy Democracy: Germany’s Energiewende to Renewables. New York: Springer.

Newton, David. 2015. Wind Energy. A reference handbook Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

Owens, Brandon. 2019. The Wind Power Story: a century of innovation that reshaped the global energy landscape. New York: Wiley/ IEEE Press.

Patterson, Walt. 1999. Transforming Electricity. Totnes: Earthscan.

Pirani, Simon. 2018. Burning Up: a global history of fossil fuel consumption London: Pluto Press.

Pirani, S. 2023a. “Wind, water, solar and socialism. Part 1: energy supply,” People & Nature, 13 September.

Pirani, S. 2023b. “Wind, water, solar and socialism. Part 2: electricity networks,” People & Nature, 14 September.

Pirani, S. 2023c. “Realizing renewable power’s potential means combating capital,” Spectre, 28 October.

Pirani, S. 2023d. “We need social change, not miracles,” The Ecologist.

Pope, Daniel. 2008. Nuclear Implosions: the rise and fall of the Washington public power supply system. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rand, J. et al. 2022. Queued Up: Characteristics of Power Plants Seeking Transmission Interconnection San Francisco: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Sapere. 1985. “Energy and the Capitalist Mode of Production” in: Les Levidow and Bob Young (eds.), Science, Technology and the Labour Process. London: Free Association Books.

Stirling, Andy and Phil Johnstone. 2018. A Global Picture of Industrial Interdependencies Between Civil and Military Nuclear Infrastructures. SPRU Working Paper 2018-13.

Sweeney, Sean et al. 2020. Transition in Trouble? The rise and fall of “community energy” in Europe. New York: Trade Unions for Energy Democracy.

Ulsrud, Kirsten. 2020. “Access to electricity for all and the role of decentralised solar power in sub-Saharan Africa,” Norwegian Journal of Geography 74.1: 54-63.

van Vuuren et al., D.P. 2018. “Alternative pathways to the 1.5°C target reduce the need for negative emission technologies,” Nature Climate Change 8: 391-397.

Our new briefing – number 15 – looks at nuclear power.

New nuclear power stations are central to the UK government’s new energy strategy. Some influential environmentalists like George Monbiot support nuclear as part of tackling the climate crisis and the Intergovernmental Committee on Climate Change (IPCC) argue that globally by 2050 energy production should 70% renewables and 30% nuclear. So why do we say that there should be no role for nuclear? In this briefing we explore the arguments around nuclear and demolish some of the myths about nuclear power.

A military technology

The raw material for nuclear weapons is produced in nuclear reactors. In the US, the UK, Russia civil nuclear power was developed after the second world war to support nuclear weapons programmes. Researchers at the University of Sussex Science Policy Research Unit have shown that to this day the main role of nuclear power in the UK main has been to subsidise nuclear weapons. Electricity consumers have paid the price through higher costs, providing a hidden subsidy for the nuclear weapons programme.

High cost

Nuclear power costs two to three times as much per unit of electrical energy than offshore wind. Onshore wind and solar is even cheaper. These comparisons don’t include the cost of decommissioning old nuclear power stations (which takes many decades) or the cost of safely storing the radioactive waste that they generate (which is necessary for thousands of years). These additional costs are born by consumers and taxpayers.

Long construction times

Since 2011 construction has started on 57 nuclear power plants around the world. Ten years later only 15 are operational, with many incurring long delays and massive overruns on predicted costs. Even advocates of nuclear power argue that it would take around 25 years for new nuclear to make a significant impact to global energy production.

Carbon free? Not at all!

To widespread consternation, the European Commission recently declared nuclear a green technology. Clearly nuclear reactions don’t generate greenhouse gases. However, it’s a myth that nuclear is a carbon free resource. Uranium mining, plant construction, which requires large amounts of concrete, and decommissioning are all carbon intensive. A 2017 report by WISE International estimated nuclear lifecycle emissions at 88–146 grams of carbon dioxide per kilowatt hour. More than ten times higher than wind with lifecycle emissions power of about 5–12 grams. Uranium fuel is scarce and carbon emissions from mining will rise as the most easily recoverable ores are mined out.

Safety

The consequences of nuclear accidents are severe. Proponents of nuclear power downplay the impact of the Chernobyl disaster in 1986 and argue that the number of deaths was small. In a scrupulous investigation, Kate Brown author of ‘Manual for Survival – A Chernobyl Guide to the Future’ has researched the decades long efforts by the old Soviet Union, and then the US, to cover up the impact of Chernobyl. She estimates that the true figure for deaths is in the range 35 – 150,000. Many nuclear plants (like Fukushima) are built close to the sea to provide water for cooling. increasingly these reactors will be at risk as sea levels rise.

Environmental impact

About 70% of uranium mining is carried out on the land of indigenous people. Mining and leaks of radiation have had a devastating effect on the environment in these areas. Building more nuclear power will result in more leakage of radioactive materials into the environment and more workers exposed to unsafe conditions and preventable deaths.

Small modular reactors

Rolls Royce is pushing for the development of small modular nuclear reactors as a response to the climate crisis. It’s argued that they could be built more quickly although this is unproven. In addition to sharing all the negative features of larger reactors, new research at Stanford University suggests that smaller reactors are less efficient and produce up to 35 times the amount of low-level radioactive waste and 30 times the amount of long lived waste compared with larger reactors.

Scotland

While Westminster is planning huge investments, the Scottish Government is currently opposed to new nuclear generation. Nevertheless, Scotland has more licensed nuclear installations per head of population than anywhere else in the world. Only one of these, Torness, is currently generating electricity, and it is scheduled to shut down in 2028. There will be strong pressure on the Scottish government to buy in to a new generation of reactors.

Alternatives

Advocates of nuclear power argue that nuclear is essential to the energy transition we need because, unlike wind and solar, it is not dependent on the weather or the time of day and so can provide a reliable base load. There are alternatives – more investment in tidal generation could also support based load supply – and the development of a smart grid involving multiple types of storage – pumped hydro, local heat pumps and battery could ensure an energy supply system that is resilient. Developing these systems alongside wind and solar would enable the energy system to be transformed much more rapidly than is possible with nuclear. A nuclear strategy is just too slow to meet the urgent need to reduce carbon emissions over the next decade. And the big sums of money being channelled in to nuclear divert investment from renewables and prevent that rapid and necessary transition.

Brian Parkin takes look at the past, present and possible futures of nuclear power in Scotland. If you want to read more on this topic do try the excellent paper by Simon Butler on ten reasons why nuclear is not the answer.

A MURKY MYSTERY

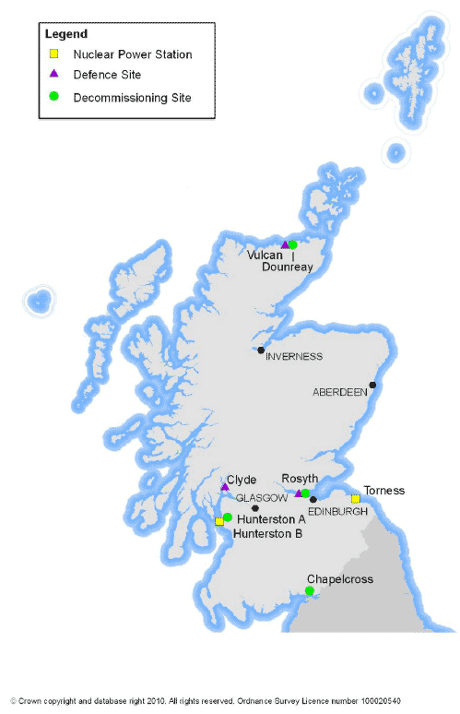

On a per head of population, Scotland has the highest concentration of nuclear installations in the world. Apart from the Advanced Gas Reactor stations (AGR’s) at Hunterston B, (Ayrshire) and Torness (East Lothian), both owned and operated by eDF, the other nuclear sites in Scotland are where nuclear power generation has ceased- but where licences remain for the continuation of nuclear power generation in the future. In total the number of nuclear sites in Scotland is five- the 2 operating reactors plus Chapelcross, Hunterston A and Dounreay in Caithness. In addition to the civilian generating sites, there are military related sites at Faslane on the Clyde, Vulcan in Caithness and Rosyth near Edinburgh. (See map).

The Chapelcross and Hunterston A stations are the now decommissioning Magnox-type reactors, ten of which formed the UK’s entrance into the world’s nuclear power race. The Magnoxs were developed over a number of years and so shared little in design and operational characteristics- but what they all shared was a graphite (carbon) core which was gas (CO2cooled) and which moderated (controlled) the speed of the Uranium235 fission- which in turn provided the heat for the steam that drove the electric turbines. All Magnox reactors are currently in the hands of the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority with the intention to render the sites decontaminated and safe- a process for which the technology is yet to be developed and the costs unknown.

The Dounreay site is the home to that ultimate nuclear fission fantasy- the Fast Breeder Reactor (FBR). The two FBR plants were intended to reproduce their own Plutonium fuel during operation- but in actual fact produced less power than consumed by their works canteens(!). The Dounreay plants present the greater decommissioning challenges due to the extremely high and extended half-life of their Plutonium fuel rods and the extreme levels of site irradiation.

GOING, GOING, GONE?

The remaining AGRs at Hunterston B and Torness, along with the other six such stations in the UK, both share a generic design fault in the form of micro and hairline cracks in their moderator block graphite cores. This has brought forward the AGR closure programme with the problem so acute that the Hunterston B station is due, on a 40% load to shut-down within the next 4 years. This will leave Scotland with the remaining Torness AGR at a 1360 MWe rating on declining load factor. According to current plans Scotland will have ceased to have any nuclear generated electricity within its borders by 2031.

But even after some 60 years of nuclear failure it might be premature to read the funeral rites.

PROBLEMS

From its very inception, nuclear power has been beset by problems. Its capital costs have historically been prone to going through the roof. Also, recurring safety issues have led to operational caution in the form of low load-factors with down-time and unscheduled outages leading to negative revenues from unreliability- all of which have made nuclear power the most expensive and unreliable on the system.

But in order to disguise the real cost of nuclear power, it has always been given a ‘first on the system/must run’ status to which in addition it has been covered by transferred subsidies from other forms of generation. In other words, nuclear power has historically inflated the overall cost of electricity to the disbenefit of the consumer. Nuclear power has been one of the biggest aggravating factors in the persistence of fuel poverty.

Also, despite a continuous torrent of glossy promotions, the nuclear industry has always hidden the cost and environmental hazards of the back-end matter of waste ‘management’; how to safely treat ‘spent’ fuel rods that represent a lethal radiological threat, plus hundreds of tonnes of reactor core material which must be ‘managed’- kept out of harms way in sealed containment for an incalculable number of years. At no stage in the planning and design of any reactor have such technological and economic challenges been factored in.

ECONOMIES OF SCALE 1: BIGGER IS BETTER

The continual economic failure of nuclear power has given rise to an enduring industry fantasy- basically by building bigger reactors with higher power densities and outputs, an ideal reactor design will become a generic model with large run replication and better reactor efficiencies. Hence some thirty years of shift-shaping a Pressurised Water Reactor of around 1,400 Megawatts output in the hope of a tooth fairy. So around the year 2000, optimum size thinking settled on the 1,600 MWe European Pressurised Water Reactor of the type now being constructed at Hinkley in Somerset- a sister of the Normandy and Finnish massive over-run and over-cost failures. So instead:

ECONOMIES OF SCALE 2: SMALL IS BEAUTIFUL: THE SMALL MODULAR REACTOR (SMR)

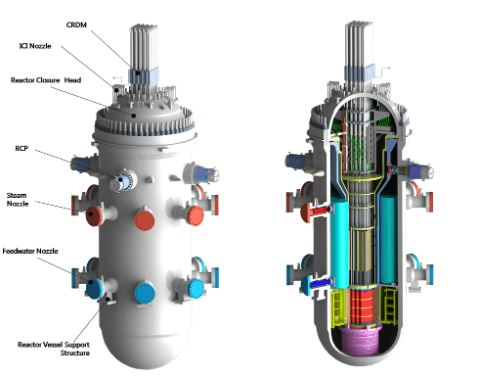

This is the obverse; a Small is Beautiful alternative to the Bigger is Better doctrine. The big sell of the SMR is a reactor that it is small, therefore requiring a smaller site footprint. It is also a modular plant that can be factory assembled and delivered with each unit- the reactor, plus cooling system components, steam turbine, pressure vessels and steam generator that when assembled form a single module that just requires being bolted into an outer shell and utility services like an Ikea kitchen flat-pack- or so the promotional goes. Also, once assembled, the reactor core can be loaded with fuel and control rods- all without the need for refuelling during the lifetime of the plant- about 40 years. The concept of the SMR is derived from earlier military Pressurised (Light) Water Reactors that were developed during the 1950-60’s to power nuclear submarines and aircraft carriers. Typically, such a reactor would be rated at around 30MW electrical output- and in the US and Russia such ‘mini’ SMR’s have been undergoing operational trials.But in many ways, the SMR is pretty well a conventional reactor sub-species in that its produced energy is derived from nuclear fission with Uranium235 as the fuel.

However, in the UK Rolls Royce have been scaling up their SMR designs to much bigger out-puts to more conventional power station ‘set’ sizes of 330-440MWe. Initially, this would seem to contradict the aim of the objective of compact size units- which to some degree is illustrated with the image of a SMR reactor encased in primary containment shell on the back of a low-loader truck. Also, the slender diameter of the reactor primary containment promotes the impression of technical simplicity-an impression dispensed by the cutaway illustration- added to which is the reality of the most demanding of shell pressures and an internal temperature hotter than the sun.

Initially, the sales spiel regarding the relative simplicity of the SMR is based on a claimed design and operational simplicity and flexibility of operation- along with claimed low capital costs of some 30% less than ‘conventional’ Pressurised Water Reactors. And it is here that SMR is now being projected as the answer to the need for a‘baseload’ component in a mainly renewables- but largely intermittent generating capacity. And with outgoing AGR nuclear stations at Hunterston and Torness- plus declining output from the gas-fired station at Peterhead, a smaller, lower cost and flexible SMR has some attraction.

Scotland; now virtually at the end of its fossil power generation history faces a future of almost unlimited renewable energy power generation technologies. Wind, wave, tidal, hydro, geo-thermal and solar power has recently begun to combine in powering Scotland for whole days without fossil or nuclear inputs. That is the future; not with a nuclear component that as ever offers jam tomorrow- but in the present offers the highest cost and most dangerous energy on the planet.

Dr Brian Parkin. July 2021.

A response to Neil Mackay’s Big Read in the Herald from Stephen McMurray and Pete Cannell

The ‘Big Read’ in the Herald newspaper on Sunday 4th October was ‘The nuclear option – can atomic power save the human race from climate change?’. In it, journalist Neil Mackay reviews a new book by US earth scientist James Lawrence Powell. Powell argues that we are at a tipping point that will lead to runaway global temperature rises unless decisive action is taken to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to zero. In this he is absolutely right. However, he goes on to argue that achieving zero carbon by replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy technologies will take too long. According to Mackay, Powell argues that achieving zero carbon in a decade by adopting renewables is just ‘infeasible’. The only serious option is to produce all our energy needs by a massive expansion in the number of nuclear power plants. Essentially, he says that we should use nuclear to buy time while renewable technologies are developed further.

Undoubtedly current energy needs could be met by nuclear. But Powell himself concedes it would take at least 25 years for this level of capacity to be reached. Indeed, construction timetables for nuclear power stations are notorious for length overruns.

Powell is not alone in arguing for nuclear as the means to end the climate crisis. However, in our view the nuclear strategy is profoundly mistaken.

Nuclear power has always been entangled with nuclear weapons programmes. The US ‘Atoms for Peace’ programme, launched at the height of the cold war promised a future of almost limitless energy. In truth the civilian reactors provided the raw material for a huge increase in the US nuclear arsenal. By 1961 the US inventory of nuclear weapons was equivalent to 1,360,000 Hiroshima bombs. In the US, the UK, Russia and elsewhere nuclear power has always been a necessary support for nuclear weapons. In the UK context researchers at the University of Sussex Science Policy Research Unit have shown that the sole case for nuclear power is to subsidise nuclear weapons. Electricity consumers are paying for the high cost of an industry that subsidises the military nuclear weapons programme.